Theology and Interpretation in the Icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God (Hierodeacon Filaretos, Monastery of the Holy Lavra, Kalavryta)

19 Αυγούστου 2020

Our Holy Church calls Our Lady, Our Mother, the sweetness of the angels, the joy of the afflicted, and the protectress of Christians. A tower embellished with gold, a city with twelve ramparts, throne dripping with the sun and seat of the King. In whatever terms we describe her, however, she remains a wonder beyond the comprehension of the human mind who suckles Christ the Lord, is a bridge between earth and heaven, the limitless hope and eternal support of every Christian.

On August 15, the Church honors the commemoration of the departure in the body of Our glorious Lady the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary. This commemoration is not one of sorrow and mourning, however, but of joy and gladness. According to Saint Andrew of Crete, this body wasn’t the earthly flesh Our Lady wore when she lived in the world, but her imperishable, spiritual, ‘altered’ body, as described by Saint Paul in his 1st Epistle to the Corinthians (15, 51-52).

We have no information concerning the Dormition of the Mother of God from the New Testament. We learn about it from ‘The Hidden Narrative of Saint John the Theologian concerning the Dormition of the Mother of God’; from ‘On the Divine Names’, by Dionysios the Areopagite; and from the ‘Praises at the Dormition’, by Fathers of the Church. This venerable tradition of the Church is summed up admirably in the exapostilario of the feast: ‘Apostles gathered from the ends of the earth, bury my body in the village of Gethsemane. And you my Son and God receive my spirit’.

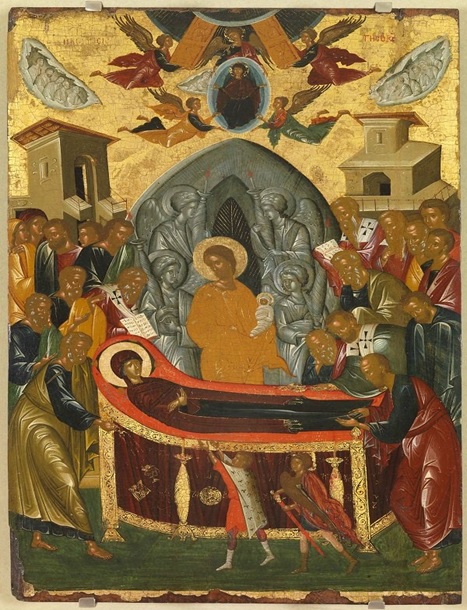

It seems that the feast in question was established in the 6th century, because around then we have the first icons with this as their subject. The festival began from the local feasts celebrated in Gethsemane in honor of Our Lady. These spread to Palestine in the 4th century and thence to East and on to the West. Some relief depictions in ivory and some wall-paintings have survived, mainly from Cappadocia and Syria. In these examples, the basic type of the icon is already established, which allows us to suppose that the beginning of the ‘narrative’ may go back to before the iconoclast controversy. In the type which was predominant in the 11th century, there is a representation of the Mother of God lying dead on a bed, with the apostles standing around and Christ behind, holding her soul. All the apostles are depicted wearing the clothing of ancient orators, while Saint Peter is often portrayed censing her head and Saint Paul bending over her feet. Christ has His face turned left, towards His mother and His body is facing right, with a certain tension in His posture. He is holding the soul of the Mother of God, which is depicted either as a small child, the head of which is covered with a scarf, or as an infant wrapped in swaddling clothes, with her arms crossed. Two full-length angels, flying symmetrically above Christ, are preparing to receive the soul of the Mother of God.

From the 11th century, various iconographical details are added, such as the angel, from among those who are surrounding Christ, who approaches Him to take the soul of the Mother of God and take it to paradise, with the Archangel Michael speeding them on their way. There are also more portrayals of women emerging from the upper room, as well as numbers of winged angels. In the 12th century, there is the first appearance of the well-known episode of the Jew, Jephomias, whose hand was severed by an angel because he attempted to desecrate the sacred coffin. Most often his severed hands are depicted on Our Lady’s death bed. This event is usually taken to symbolize the ‘all-pure and incorruptible’ nature of the Mother of God, which prefigures and realizes the Church of God, which must not be polluted by anyone, but must remain ‘ever holy and spotless’, as the ark of salvation.

In the mid-14th century, the depiction became fixed in the form it’s known today, which has a greater number of details and variations. Related subjects which have been added are the burial of Our Lady and her assumption, the latter of which is accepted as dogma only by the Church of Rome. It is worthy noting the ways in which the icon of the Dormition has continually been enriched, with the mandorla of Christ, the seraphim above Him, the hierarchs and hymnographers (as regards hierarchs, there were four present at the Dormition: Saint James, the Brother of Our Lord, Saint Ierotheos, the first bishop of Athens, Saint Dionysios the Areopagite and Saint Timothy the Apostle. As regards the hymnographers who are usually depicted, according to Dionysios from Fournas, these are Saint Kosmas the Melodist of Maium, who wrote the first canon for the feast in tone 1 and Saint John the Damascan, who wrote the second in tone 4. Both hymnographers are holding long scrolls on which are written excerpts from their hymns. According to Saint John the Damascan the semi-circle denoting the sky, the women mourning the Mother of God, the buildings, which play an important role in defining the perspective in the icon, the candle under her feet, the side elements (such as the clouds, the Jew and so on), the souls of the apostles in the form of busts in clouds) all come together to honor the ‘sleeping’ Mother of God.

The depiction of the Dormition of the Mother of God is the last of the subjects of the Twelve Feasts, the most important festivals of the Church and are used for the icons in the apses and on the highest parts of the walls of the church. Some of the most characteristic examples of this particular feast are to be found in the Monastery of Dafni (11th c.), Saint Nicholas Kaznitsis, in Kastoria (1160-1180) and Martona, in Palermo, Sicily (1146-1151).

The Virgin Mary is the fruit of the tree of the blessed and righteous in the Old Testament, the sealed gate of the East, according to the Prophet Ezekiel, the comfort, the harbor, the refuge of every suffering soul. This is why, in the conscience of ordinary Orthodox people, this feast is the second Easter, the summer Pascha. The first fruit of the ‘beginning of the other, eternal life’, which we celebrate at Easter, is the glory of Our Most Holy Lady, the Mother of God.