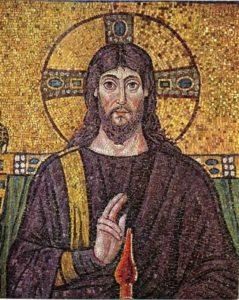

Christ as Word (John Meyendorff)

31 Μαΐου 2016

Since you have learned to hear, Slavic people,

Hear the Word, for it came from God,

The Word nourishing human souls,

The Word strengthening heart and mind….

(St Cyril and St Methodius, Prologue to the Gospels)

During their famous mission to “Great Moravia, “the two brothers of Thessalonica, St Cyril (known also as Constantine “the Philosopher” before his tonsure as a monk) and St Methodius, were faced with strong opposition: the German clergy, who were competing for the souls of the Slavic converts, affirmed that scripture could be read only in three languages –Hebrew, Greek and Latin– and that translation into Slavic was inadmissible. So, the two Byzantine missionaries became involved in a controversy that anticipated the great debates of the Reformation period on the issue of whether scripture should be made available to the laity. Indeed, their entire missionary endeavour was based upon the translation of the Bible and the Liturgy of the Orthodox Church into a language understood by their converts. They thus created “Church Slavonic” -the common vehicle of Christian culture among Orthodox Slavs.

In a “prologue’ in verse (Proglas), which preceded their translation of the Gospel Lectionary, they expressed the meaning of their mission by developing a theology of the word.(1) Both brothers read scripture in the light of the Greek patristic tradition in which they were trained. It inspired that which is often referred to as the “Cyrillo-Mefhodian” ideology, based on the belief that the Christian faith must become incarned (or indigenised) in order to produce authentic fruits of dynamic human cooperation with God in building up a Christian society and a Christian culture.

In this essay we are attempting to convey some of the meaning of that theological and spiritual tradition, not only in its historical dimension, as it inspired St Cyril and St Methodius eleven centuries ago, but as it can provide solutions for contemporary issues as well.

On the most solemn moment of the liturgical year, at the liturgy on paschal night, the church proclaims, through the prologue of St Johns Gospel “In the beginning was the Word-Logos.” In our secular civilization the term Logos has not become a totally foreign word: we meet it whenever we speak of biology, of psycho-logy, or whenever we affirm that our words or actions are logical. Our children learn all these terms in the most secular of our schools. They are highly respectable terms, sometimes opposed to what one calls religion because they are scientific terms; they designate one’s knowledge of matter, of life, of the human self, while religion–purportedly deals only wifh guesses, or perhaps with myths, or at least, with symbols. So Logos stands or knowledge for understanding, for meaning. And it is indeed the most daring, the most challenging, the most affirmative of all the words of scripture, which says:

In the beginning was the Logos

And the Logos was with God

And the Logos was God (John 1: 1)

This means that the key to all knowledge, to all understanding of anything that can be learned and, indeed, the meaning of everything that exists is in God, the Logos.

All things were made by Him; and without

Him was not anything made that was made.

In creation, however, there are also powers of darkness, of disorder, of chaos, of resistance to the Logos. These illogical powers are also mentioned in the same prologue of John’s Gospel:

That was the true light, which lighteth every

man that cometh into the world.

He was in the world, and the world

was made by Him, and the world knew him not.

Nevertheless, the unique event that expresses the whole content of the Chtistian claim did occur:

The Logos was made flesh, and dwelt among us,

And we beheld his glory, the glory as of the

Only Begotten of the Father

Full of grace and truth.

Very often we tend to consider John’s prologue as somehow peripheral to the basic content of the gospel, as if it was a somehow arlificial and dated attempt at explaining philosophically the identity of Christ. Logos, we are told, is a concept coming from Stoic philosophy. It is foreign to Hebrew thought and, therefore, does not belong to the original Christian gospel. Most modern exegets agree, however, that, although St John deliberately uses a term that was familiar in the Hellenistic world, where early Christian communities were beginning to spread, he is basically inspired in his Logos-theology by the image of divine wisdom in Proverbs 8:

The Lord made me the beginning of his ways for his works.

He established me before time was in the beginning,

before he made the earth:

Even before he made the depths; before the

fountains of water came forth;

Before the mountains were settled, and before all

hills, he begets me;

The Lord made countries and uninhabited tracts,

and the highest inhabited parts of the world.

When he prepared the heaven, I was present with him,

And when he prepared his throne upon the winds:

And when he strengthened the clouds above;

and when he secured the fountains of the earth;

And when he strengthened the foundations of the earth:

I was with him, suiting myself to him,

I was that wherein he took delight,

And daily I rejoiced in his presence continually.

For he rejoiced when he had completed the world,

and rejoiced among the children of men.

(Prov. 8:22-31, LXX)

The synoptic gospels begin their narratives with historical events: the birth of Jesus, his baptism and the beginning of his preaching ministry. In contrast, John starts with a deliberate parallel between the story of creation and that of the new creation in Christ: “In the beginning God created heaven and earth” (Gen. 1:1). “In the beginning was the Logos” (John 1:1).

Our usual modern methodology in studying the New Testament leads us to see in John’s Gospel a theological interpretation of the already existing and basic narrative of the synoptics. Historically, this is undoubtedly true. The liturgical tradition, however, interprets the Gospel of John, as the foundation of the church’s kerygma: in the Orthodox Church, the prologue of John is read during the liturgy of the paschal night and thus begins the cycle of scripture readings for the entire liturgical year. What does that liturgical usage imply? It implies that in the resurrection of Jesus, the empty tomb, the joy of the mysterious encounters between the Risen Lord and his disciples, there is the revelation of the meaning of creation. The Genesis story itself cannot be understood without the revelation-in Jesus-of what was the real original purpose of God’s creative acts: the new creation, the new humanity, the new cosmos, which are manifested in the resurrection of Jesus, are what God originally intended. As Proverbs says, God “rejoiced when he had completed the world and rejoiced among the children of men” (8:31). But human beings rejected God’s fellowship; their mutual rejoicing was replaced with a proud self-determination of humankind, which could only provoke God’s anger: but here, in Jesus, there is a new beginning, a new joy. And all of this is possible because the new creation comes by the will of the same God and is realized by the same Logos.

Here is, therefore, the first major implication of John’s prologue: Christ, being the Logos, is not only the saviour of individual souls; he does not only reveal a

code of ethics, or a true philosophy: he is the saviour and the meaning of all of creation.

The consequences of this fact for Christian mission in the world are, of course, tremendous. The Christian church is called not only to save human individuals from the world, but to save the world itself. For if Christians know Christ, they are also initiated into the meaning of all things, they possess an ultimate key certainly not for a scientific understanding of the cosmos, but for getting a sense of what creation is about.

One of the most important points that the early church understood in light of its doctrine of the Logos, is that the world, being created by God, is not divine in itself. The worship of cosmic powers-the stars, thunder, or individual animals-was denounced as idolatry by the early Christians. They certainly recognized spiritual realities behind these cosmic elements, but these realities were created, and frequently demonic, especially when they demanded, or simply ptovoked worship of themselves.

So the first, and initial step of “every man coming into the world” is an exorcism of himself, and of the world around him. The liturgy of baptism begins with exorcisms and includes an exorcism of the water used for the baptismal immersion.

The exorcism of the catechumens includes the definition of Satan as the “tyrant,” a technical term designating usurpers, opposed to the legitimate authority in human society. The power of Satan is not only evil and deadly: it represents an usurpation of the legitimate authority of God. It is also “tyrannic” in the sense that it enslaves, whereas God’s power frees: the catechumen cannot become the adopted child of God unless he is first liberated from Satan’s tyranny.

The same ideas of exorcism and liberation are beautifully expressed in the prayer of blessing the baptismal water:

O Master, Thou couldst not endure to behold mankind oppressed by the Devil; but Thou didst come, and didst save us. We confess Thy grace. We proclaim Thy mercy. We conceal not Thy gracious acts… Thou didsf hallow the streams of Jordan, sending down upon them from heaven Thy Holy Spirit, and didst crush the heads of the dragons who lurked there.

The ideas of exorcism and liberation are followed with a joyous confession, that creation, in its spiritual and material substance, is called again to become a paradise of freedom and life:

O Master of all, show this water to be the water of redemption, the water of sanctification, the purification of flesh and spirit, the loosing of bonds, the remission of sins, the illumination of the soul, the laver of regeneration, the renewal of the Spirit, the gift of adoption to sonship, the garment of incorruption, the fountain of life.

Therefore, the Christian should not fear the elements of the world. They have neither divine nor magic power in themselves, but Ihey were created by God through the Logos and, through the power of the Spirit, are recovering their original purpose and function. Humankind is called to control them, instead of being enslaved by them. This is the meaning of the various rites of blessing and sanctification–of the water, of food, of the eucharistic elements themselves: the whole of creation is called to its “logical” purpose under God, and also under human beings, who, through the power of God, must exercise dominion over creation (Gen, l28).

So, the Word of God, as Logos, is not only spoken by the Christian. The Christian mission is a mission of renewal of creation, precisely because the same Logos was the Creator in the beginning and now comes again into the world, as its Saviour, and because, for God, speaking and acting is the same thing.

The idea of renewal, or new creation, has been the subject of many misunderstandings among modern theologians. Defined in terms of the “depth” of things by Tillich and in terms of an evolution bound towards Omega point by Teilhard de Chardin, the “logical” structure of the cosmos was often reduced to secular categories. As a result, the renewal itself was seen in terms of a betterment of the existing world, of Christian participation in the processes that purportedly lead to such betterment. As a result, Christians identified themselves with causes and ideologies, which neither in their substance nor in their ideals were really new.

Let us hope that the dream that led so many sincere Christians to visualize new creation simply in terms of social revolution, or psychological adjustment, has now been seen for what it always was: a basic misunderstanding of the biblical idea of creation. Actually, the misunderstanding is as old as Christian Platonism: the great Origen, in the third century, had refused to take this biblical idea seriously and as a result identified human destiny with “eternal cycles” of spirits, falling away then returning to the contemplation of God’s essence. Nothing really new could ever happen in this cyclical movement. But the God of Abraham, of Isaac and of Jacob is above all human contemplation: He is the one who is, the “all-powerful,” the Pantokrator, the Creator. And his Logos is “with him,” uncreated and consubstantial. Only through this uncreated Logos and the Spirit, which realized this presence, can fallen creation be renewed –not through the creatures’ own efforts, or any other creaturely development. Already in 1967, at the height of the secularist movement in western theology, an Orthodox bishop, speaking at the Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Uppsala said:

(The Spirit) is the Presence of God-with-us “bearing witness with our spirit” (Rom. 8:16). Without him God is far away; Christ belongs to the past, and the Gospel is a dead letter, the Church is merely an organization, authority is domination, mission is propaganda, worship is an evocation, and Christian action is slave-morality.(2)

Christian mission consists in revealing and re-enacting the divine and uncreated, transcendent and re-creating power of the One Logos in the world. This is not simply “speaking,” or “doing.” It is the reality of what Paul means when he writes: “We are labourers together with God” (I Cor. 3:9). To that task, humankind was destined at their creation, when they received the dignity, unique among all creatures, of “belonging” to God (John 1:11), of possessing a “logos’ of their own, which placed them in a natural relation of fellowship and communion with the creator.

Christian theology has found a variety of formulations for the idea that between the Creator and the creatures, there is a relationship closer than that of cause and effect. This is, of course, eminently true of humankind, who have been established as the head and centre of creation.

The Bible speaks first of all of the human being as “image of God.” The New Testament has also a great number of terms signifying the communion that existed between God and humankind at the beginning, which was ruptured by sin and again restored in Christ. The preoccupation of theologians at all times was to maintain the two antinomical affirmations of the Christian revelation:

God is absolutely different from creation; God is transcendent, the “only one who truly exists”; unknowable in essence; adequately qualified in negative terms only, inasmuch as all positive affirmations of human mind concern the things created by God: as compared to these creations, God can only be the other;

God is present in his creatures; can be seen through them; God also “came into his own,” “became flesh” and, in the unique person of Christ occurred a union of humanity and divinity so close, so inseparable, that it can even be said that the Lord of glory was crucified (see I Cor or. 2:8).

The antinomy of transcendence and immanence must be maintained in Christian theology if one is to avoid pantheism on one side and the transformation of God into a philosophical abstraction on the other.

The theology of the divine Logos in its relation to the many logoi of creation, the “seeds” that provide a divine basis for everything that exists by the will of God, is the model most frequently used by the fathers to express the relationship between God and creation. The fact that this theology is already that of John’s prologue to his Gospel and that it was familiar to the intellectual worldview of Greek philosophy as well, made it a convenient means of communication between the church and the world: this communication, however, had also to express the absolute uniqueness of the God of the Bible, the personal Creator and the personal Saviour of the world.

No philosophy, except for Christianity, has ever identified the Logos as the very person of God, whose relation to creatures is to be defined in terms of his will for them to exist not only outside of himself, but in a sense in himself also, as objects in whose existence he is personally involved. God indeed is not only the Creator of the world, but he also “so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son, so that those who believe in him may have everlasting life.

Therefore, the Word of God, which created the universe, is not simply a prime mover or an abstract cause. Things were created not only by him, but in him (Col. 1:16). He was before they came into existence, and their existence possess spiritual roots in him. This is how the great Maximus the Confessor visualizes not only the unique transcendent Logos of God, but also the logoi of individual creatures, who depend on him and pre-exist in him:

We believe that the logos of the angels preceeded their creation; (we believe) that the logos of each essence and of each power which constitute the world above, the logos of men, the logos of all that to which God gave being–and it is impossible to enumerate all things– is unspeakable and incomprehensible in its infinite transcendence, being greater than any creature and any created distinction and difference; but this same Logos is manifested and multiplied in a way suitable to the Good, in all the beings who come from him according to the analogy of each, and recapitulates all things in himself (Chapters on Love, III, 25, P. G., 91:1024 BC).

This is not simply the revival of a platonic “world of ideas,” but also–as we have noted before–a rewording of the several chapters of the Old Testament “Wisdom literature,” which we also find in Ephesians 3: “the mystery which from the beginning of the world has been hid in God, who created all things; … the manifold wisdom of God, according to the eternal purpose which he realized in Christ Jesus our Lord” (9-1I).

What this tells us is that, in the divine Logos, the world has a meaning, a purpose and a design that existed before creation itself.

But this is not a naive and rosy picture of creation. Death, sin, chaos, disintegration are also there. There is no way of reaching back to God, to the original roots of creation, to a restoration of the meaning of things, without acknowledging the tragedy of death. Actually, Christians can have an even fuller understanding of the tragedy of death, of the existential anguish, of the various “dead ends” of the present state of the world, than the secular existentialists. The secular existentialists describe what is, but Christians know what should be, and therefore are even better aware of Ihe chaotic, bloody, and indeed illogical tragedy of the world’s present condition.

According to the same Maximus the Confessor, the world was created not as a fixed and stable reality, but as movement. The very word nature is defined by him, as movement, or, more precisely, as “the logos of its essential activity” (Amb., 1057 B). This movement was beneficial, creative and, therefore, “natural” as long as it followed its logos of being. The French translate literally: raison d’être. This raison d’être was, of course, the divine Logos himself. Today, however, man in his actions is possessed by the irrational imagination of the passions, deceived by concupiscence, or preoccupied either by the contrivances of sciences because of his needs, or by the desire to learn the principles of nature according to its laws. None of these compulsions existed for man originally, since he was above everything. For thus man must have been at the beginning: in no way distracted by what was beneath him or around him or near him, and desiring perfection in nothing except irresistible movement, with all the strength of love towards the one who was above him, i.e., God (Amb. 1353 C).

Is this an appeal by St Maximus to stoic apathy, to indifference to the world? Certainly not, for two reasons:

1) The ultimate goal –life in the Logos– is not fixity, nor passive contemplation: it is movement, personal relationship, encounter in love and, therefore, an eternal translation from joy to joy, from glory to glory. The kingdom of God is not static immobility but joy, creativity and love.

2) What is to be rejected is a utilitarian pre-occupation with the world, based on the desire to use the world as a tool for survival. In Maximus, as in the entire mainstream of eastern patristic tradition, mortality (not “inherited guilt”) is the great consequence of Adam’s sin. The misery of the present world resides in its corruptibility, and hence the constant signs of insecurity, under which humanity exists: the world as a whole, and each one of us individually, is engaged (how unsuccessfully) in a struggle for survival, which consists partly in finding means of prolonging our life, and partly in discovering other means that would neutralize or liquidate those who (so we believe) threaten our existence. Mortality is thus the real cause of our sinful situation. Self-defence, self-affirmation –at the expense of others– is that which determines the existence of our present illogical world. So when Maximus calls us to abandon our pre-occupation with science, with concupiscence, with greed, it is because he wants to free us from our utilitarian dependence upon that which should not be our real tools of survival. He is certainly for a free, conscious and creative control of the universe by man, who bears the Creator’s image and therefore a co-responsibility for creation, but against our enslavement by the world.

His description of human beings in the fallen world presents the picture of a harmony destroyed. Originally God the Logos created all things in harmony. There was, for instance, harmony between:

Things created and the uncreated God;

Things intelligible and things tangible;

Heaven and earth;

Paradise and universe;

Male and female.

These natural dualities were to be pceserved in harmony, but were in fact transformed into tension, contradiction and incompatibility. The fall was a disruption of creation, a tum of its “logical” nature towards tragic illogicality, which in turn leads to corruption and death.

It is in the light of this disruption of the original meaning and order of things, that Maximus, together with the entire patristic tradition, envisions the great event of Ihe incarnation: “The Logos became flesh.”

This means that the very model of creation, the origin and criterion of harmony and order, has assumed that which had fallen into disorder and disharmony. And so between God and the creatures, between things intelligible and tangible, between heaven and earth, between paradise and universe, between male and female, there is harmony again, but only in Jesus Christ, the incarnate Logos.

It is not possible for us here to devetop further a theology of the incarnation, but I wish to emphasize only one point, which is directly related to our theme, “Christ as Logos:

If the divine Logos becomes flesh, there is no more and can never be an incompatibility between divinity and humanity. They cease to be mutually exclusive, For us Christians God is not only in heaven, he is in the flesh: He is with us first because he is the Logos and model of creation, and second because he became man. In Christ, we see God as the perfect man. Our God is not “somewhere” -in heaven. People have seen him, we see him –in Jesus of Nazareth.

More so, the Logos, as divine person, must be seen as the personal centre of Christ’s human activity. The Nicean Creed teaches us that the Son of God, consubstantial with the Father, “was bom, suffered…was buried.” He is the subject of these very human experiences of Jesus Christ. Therefore, he also shares our human experiences. The Logos is personally the subject of the death that took place at Golgotha, and it is precisely because it was the death of the Logos incarnate not only the death of a human individual that it leads to the resurrection. He is therefore wilth us at the hour of our death, and wills to lead us to life (if we will it also).

In the incamation of the Logos, God did not only speak; he did not only forgive: He loved and shared every human experience, excluding only sin, but including death and ultimate suffering. In the beginning “without him was not anything made that was made.” And now, in his second and new creation, he left nothing that had been created, outside of himself, not even death, as fallen man’s condition, which now –if we betieve in Christ– can become for us “a blessed repose” and nof anymore a tragedy.

The problem, of course, with the modern “death of God” theologians is that their slogan means something different to what was meant by Cyril of Alexandria, Their concern is to humanize God, and then to conclude that “he manifests himself to us in and through secular events.(3) This is in fact exactly the opposite of what the “Death of God” on Golgotha really means: the Logos dies on the cross, so that death may be destroyed. After Golgotha, death ceases to be a “secular event.” It becomes a sacrament, a transformation of the prosaic, physical disintegration of tissues, into a paschal event leading to freedom and resurrection. The Logos, by assuming humanity, has given us the power to transcend secular events. They still happen, of course, but we have access to God outside of them, and therefore we are free from them.

We still have a mission to the secular world, of course-a mission to those who do not see the Logos either in creation or in his incarnation. But the dynamism, the power, the meaning of our mission can be discovered only in our independence from and power to transcend secular events.

“God became man,” Athanasius said, not to disappear as God, but “so that man may become God.” The Christian gospel, the “good news” consists in that, and only in that.

The theology of the word of God, as Logos, especially in the light of the incarnation, has major practical implications in terms of the Christian mission and the life of the Christian church. If the Logos is the Creator, the meaning and the model of the entire creation, his body, the church, necessarily assumes a co-responsibility, one can also say of co-creativity, in the world as a whole. This is indeed the essential expression of the church’s catholicity, its involvement in the wholeness of creation, because the Creator himself is its head.

First of all, Christian responsibility is a responsibility to all people. In a sermon at St Mary the Virgin, in Oxford, C. S. Lewis once said:

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most interesting person you tatk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or another of these destinations. If is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics.

Christian responsibility is not limited to “spiritual matters,” or to the concept of “right belief” understood, as a set of concepts perceived by intelligence alone. The word of God is not communicated only in human words: it is a communication of life itself. This is why the Catholic Church throughout the ages has known how to “spread the word” through the holiness of its members, through poetry, through images, through music, i.e., by manifesting the harmony, the order, the truth of God’s creation.

May I submit at this point that it is a recovery of this sense of harmony and beauty that is needed more than anything today for the Christian message to be heard again by our contemporaries. And this recovery is possible only on the basis of a renewed perception of the Logos, as both Creator and Redeemer.

Christians never commit a greater spiritual crime than when they accept the dualism of grace and nature, the sacred and the secular, when they concede that there is an autonomous natural sphere that can possess its own beauty (different from the “religious” one), its own harmony (created by God, but somehow independent of Christ). It is time that we start affirming and proclaiming that God is the creator of beauty, and that nothing created can be legitimately “secularised.” (As Dostoyevsky said, this beauty, created by God, will ultimately save the world.)

We all know, for example, how –throughout the centuries– the church made use of matter, of music and of images in manifesting the presence of the kingdom of God in the liturgy. How, through the rites of sanctification and blessing, it has asserted its claim to universality, encompassing the entire cosmic reality. Indeed, nothing of the “old creation” can be left outside of the “new”‘!

This does not mean, however, that any cultural form contributes to a manifestation of “new creation.” or that any style of art is as able as the Romanesque, the Gothic, or the Byzantine, to reflect the mystery of the incarnation. The drama of a secularised culture, which excludes the logos of creation and builds its forms upon the reaction and intuitions of “autonomous” humankind, has gone very deep in our world today. A process of selection, of purification and redemption, similar to the one that confronted the fathers of the church when they faced the gigantic task of converting the Greco-Roman world to Christ, faces us again today. Of course, our task is much more difticult, because the world we face is a post-Christian world: it pretends to know the Christian norms and to reject them deliberately. Christianity has tragically lost its novelty: it smells a reactionary past. A simple return to ancient liturgy, to ancient art, to ancient music is therefore both insufficient in itself and may lead to further compromising the ever-new, creative nature of the Christian faith.

Personally, I think that antiquarian conservatism, a “return” to the past, is often better than bad improvisations. But, clearly, if Maximus the Confessor was right in defining the “logos of being” as a movement, one should recognize that Christian mission requires new forms, new ways of including the whole of today’s humanity, of today’s world into its realm. But these new forms cannot simply be imported as such from the fallen world, uncritically; they must be adapted to the unchanging content of the Christian gospel and manifest this content in a way that would be consistent with the holy tradition of the one catholic tradition. So, authentic Christian creativity requires this effort of selection, of discernment, as well as boldness in accepting new things.

In their own days, Saints Cyril and Methodius were eminent witnesses of such creativity, not only because –as so many missionaries before and after them– they were able, culturally and linguistically, to identify with a social group that needed to hear the gospel, but because they were able to be both traditional and innovative, both faithful and critical. As Orthodox Byzantines, they opposed, as an obvious “innovation,” the interpolation of the common creed with the unfortunate Filioque clause, but they were respectful of the venerable Church of Rome (which helped them against the Germans) and translated not only the Byzantine liturgy, but also the Latin rite into Slavic. The authentic “catholicity” and dynamism of their ministry should remain as our model even today. To emulate that model is the best way of commemorating the 1100th anniversary of St Methodius’ death.