Smyrna 1922

15 Σεπτεμβρίου 2011

Smyrna was the wealthiest of Ottoman cities, located on Turkey’s Aegean coast, it embodied that empire’s best qualities of cosmopolitanism and religious tolerance. The city was known as the ‘Pearl of the Orient’.

Smyna had some of the most luxurious department stores, cinemas, opera houses in the world. While Greeks (320,000) predominated, the city also housed sizeable Armenian (10,000), Jewish, Turkish (140,000), European and American populations. Smyrna was a place where those people lived in peace.

The Levantines were by far the richest community, with the largest stake in every commercial activity. They were of British and European descent and had lived in Smyrna since the reign of King George III (1760), and led a charmed existence. Life was a glittering round of tennis parties, balls, yachting and picnics accompanied by bouzouki players.

The decentralised Ottoman system of government had allowed Smyrna to function freely through World War I, and was largely untouched by the tragedies of the Great War. The city’s Ottoman governor, Rahmi Bey, a genial Anglophile, had even protected the Armenian population from the deportations and massacres of 1915, and that was no mean feat.

28 July 1914

The Great War began

1 August 1914

Germany and the Ottoman Empire signed a secret alliance treaty

23 January 1915

Greece’s Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos was offered ‘most important territorial compensation for Greece on the coast of Asia Minor’ on condition that Greece joined the war on the side of the allies. Smyrna along with all the rich farmland that surrounded the city, was to be handed to him on a plate. Britain’s plans for an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula viewed that it would be invaluable to have Greece on board as an ally. He took the bait.

11 November 1918

Fighting ended: treaties were to be signed, borders redrawn, new countries created, scores settled.

18 January 1919-21 January 1920

Paris peace conference

Venizelos lobbied for the dismemberment of the Ottoman empire and an expanded Hellas (the Megali Idea) that would include the Greek communities of Northern Epirus, Thrace and Asia Minor. The Idea was the core concept of Greek nationalism: to restore a Greater Greece on both sides of the Aegean, incorporate those territories with Greek populations outside the borders of the Kingdom of Greece, and create a Christian Empire in Asia Minor. There were 2.5 million Greeks in the Ottoman Empire.

There was concern for Greek safety and that was well-founded given the events of 1915 when an extreme nationalist group unleashed genocidal policies against the minorities in the Ottoman Empire, and hundreds of thousands of people were slaughtered. While the Armenian Massacre is the best known of these events, there were also atrocities towards Greeks in Pontus and western Anatolia. Venizelos stated to a British newspaper that:

Lloyd George was convinced that aligning Britain with what he expected to be the winning side would serve Britain’s interests well. (At stake were concessions to the region’s rich oil supplies.) He received and ignored wise counsel to the contrary.

Greece received an order to land in Smyrna by the Triple Entente as part of the partition of Turkey. Thus began a three-year-long war between Greek Christians and Turkish Muslims. The Ottoman government collapsed completely and the Empire was divided amongst the victorious Entente powers with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920. However that treaty was never ratified by either party.

15 May 1919

Twenty thousand Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna and took control of the city and its surroundings under cover of the Greek, French, and British navies. Greek troops proceeded to loot the Turkish quarter, killing hundreds and thereby enraging Turkish nationalists.

Mustafa Kemal had come through WWI with an unblemished record. He had fought with stubborn determination against Anzac forces in Gallipoli and worked hard to stop the British advance in the Middle East.

The military operations of the Greco-Turkish war can be roughly divided into three phases: 1. May 1919 to October 1920, encompasses the Greek Landings in Asia Minor and their consolidation along the Aegean Coast; 2. October 1920 to August 1921 was characterised by Greek offensive operations; and 3. August 1922 when the strategic initiative was held by the Turkish Army.

26 August 1922

Turkish counter-attack

The Turkish army, well trained and supplied by France and Italy, finally launched a counter-attack, and the major Greek defence positions were overrun, and Afyon fell next day. On 30 August, the 200,000 strong Greek army was routed at the Battle of Dumlupinar, with half of its soldiers captured or slain and equipment lost. This date is celebrated as Victory Day, a national holiday in Turkey. On 1 September, Kemal issued his famous order: “Armies, your first goal is the Mediterranean, Forward!”

2 September

Eskisehir was captured. Balikesir and Bilecik were taken on 6 September, and Aydin the next day. Manisa was taken on 8 September. The government in Athens resigned.

Turkish cavalry entered into Smyrna on 9 September. Gemlik and Mudanya fell on 11 September, with an entire Greek division surrendering. Expulsion of the Greek Army from Anatolia was completed in 14 September. The offensive was a success, and within two weeks the Turks drove the Greek army back to the Mediterranean Sea.

The first year of the war the Greeks were helped by the fact that British troops invaded the Straits, the richest and most populous part of Turkey, and French troops attacked the Turkish army from the south.This was as great a level of support Greece could have asked for. In addition, Turkish troops also had to fight with the Armenian army on a third front. These fronts though were soon settled and the Kemalist forces could be turned in defence against the Greek intrusion in larger numbers. Of course, a host of other factors came into play that are too numerous for this account.

6 September 1922

There were 21 war ships in the harbour: 11 British, 5 French, 1 Italian, 2 US with more to come.

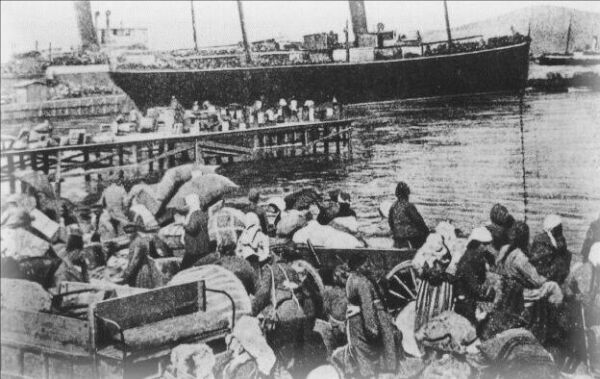

Some 50,000 Greek troops and thousands of refugees in their wake poured into Smyrna and congregated on the quay side. The interior was in complete turmoil. Greeks ships in the bay were taking away the soldiers as quickly as they could be embarked.

7 September 1922

The allies had strict orders not to intervene in Turkish internal affairs. Their responsibilities lay with their national citizens.

There were some 150,000 homeless refugees were in Smyrna.

8 September 1922

Troops were landed in Smyrna: American 35 soldiers and British 200 marines.

9 September 1922

Turkish cavalry entered into Smyrna. (p. 3) By dusk the Turkish army had approached the city from all sides and violence broke out.

There was looting by rich and poor alike. large numbers of Greek soldiers had not managed to embark, and they settled old scores by a killing spree.

10 September 1922

There was large scale looting, raping, mutilating, killing of Armenians and Greeks. The Armenian quarter was systematically ransacked.

Kemal’s cortege entered Smyrna through the Turkish quarter where the cavalry awaited him. General Noureddin was appointed governor – a cruel man with an intense hatred of foreigners.

A battle raged with a battalion of 6,000 Greek soldiers heading to the coast. That last vestige of the Greek army surrendered and were taken prisoners of war.

Metropolitan Chryssostom was murdered by a mob. There was no authority over men brutalised by years of war. Atrocities were committed in full view of the war ships. The streets and harbour were filling with bloated corpses.

11 September 1922

The situation was deteriorating as more and more refugees made their way to Smyrna.

12 September 1922

More and more homeless terror stricken refugees continued to arrive to camp out in streets. They were immediate victims of lawless elements of the Turkish army.

At that time some 7,000 British troops were stationed in Constantinople. Kemal stated: “We must have our capital and if Western Powers will not hand it over, I shall be obliged to march on Constantinople”. (p. 293)

“Smyrna was plunged into anarchy – desultory shooting, looting and rape all over the place”. (p. 296)

The allied ships remained under orders not to take off any Greeks or Armenians. However, it is likely that the Turks would not have permitted them to leave.

13 September 1922

The allies began evacuating their nationals.

The city’s population swelled to over 700,000 people. Yet, Smyrna’s non-Muslims were confident that the warships of the Allied fleet would protect them. They hoped Kemal would view this still prosperous city as an asset to the new republic. They were, however, unprepared for the horror unleashed upon them.

Turkish troops set the Armenian quarter alight. (This is denied by Turkish historians who claim that there was sabotage by Greeks and Armenians.) The wind blew sharply from the east and as the fire spread thousands of refugees headed to the quay side. The quay side became crowded with half a million refugees with the fires raging behind them. The city burned for four days.

The quay side was a scene of total misery 3.2-km long and as a wide as a football pitch. These people were in danger of being burned alive as the fire had reached the waterfront. These hapless people had three options: fire, Turks, ocean.

The ships moved 250 yards further out to avoid the intense heat. The ships’ bands struck-up tunes to drown-out the screams and shrill cries of a frantic mob on the quay side.

A British admiral had a dramatic change of heart and ordered all available boats to be lowered and dispatched to the quay side. There followed total chaos. Yet, one by one the ships were filled to overflowing with Greeks and Armenians.

The harbour and streets were filled with bloated corpses: people, dogs, horses. There was the stench of burning flesh.

14 September 1922

The rescue mission continued and space was found for 20,000 people. The war ships sailed to Athens which was already crowded with refugees and not equipped to deal with an influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees.

15 – 18 September 1922

Refugees continued to arrive in Smyrna. There was hunger and thirst and a sanitary crisis.

Kemal decreed that any refuge in Smyrna on 1 October would be deported to central Anatolia. But the deportations began immediately. All Christians of military age were deemed an enemy. These forced marches were like that of the deportations of 1915.

19 – 30 September 1922

Asa K. Jennings stepped to the fore. An American employee of the YMCA, his efforts stirred the Allies and the Greek government into rescuing half a million refugees. He found himself blagging his way into a temporary appointment as a Greek admiral in order to oversee the evacuation of thousands of desperate refugees – an extraordinary story. General Noureddin was persuaded to extend the deadline by another 8 days. (pp. 352-381)

This lone American citizen – a YMCA worker who possessed no government authority – masterminded an incredible humanitarian exodus that saved over 300,000 lives from certain death. He thereafter negotiated for the rescue of over a million more Greeks and Armenians from Turkey.

This stunning act of rescue was by Asa K. Jennings: a diminutive, humble man motivated purely by his own spiritual vision. This is one of the most incredible single-handed rescues of all time – and yet is virtually unknown. However, the complicated political and economic historical context that led to this tragedy is as relevant today as the current world situation in the Middle East.

Ultimately 100,000 people were killed and 160,000 deported to the interior