Saint Syncletica (January 5)

5 Ιανουαρίου 2011

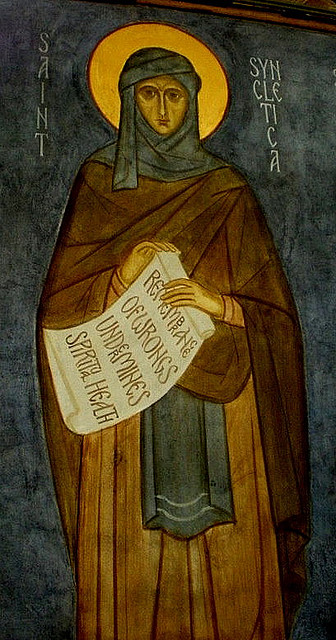

St Syncletica. Fresco by Elder Sophrony Sakharov at the refectory of St John the Baptist Monastery in Essex.

Our holy mother Syncletica was born at Alexandria in the course of the fourth century to rich and devout parents, who came originally from Macedonia. From her youth, she had been seen as an excellent match on account of her great beauty, intelligence and virtues, and she had many suitors; but she remained deaf and blind to every worldly attraction, for she aspired only to spiritual marriage to Christ, the heavenly Bridegroom. Bringing her flesh into subjection by fasting and austerities of every kind, she constantly gathered her spirit in the depths of her heart and cried out night and day: My Beloved is mine, and I am His (Song of Songs 2:16).

On the death of her parents, she distributed her great fortune to the poor and then, accompanied by her blind sister, she fled far from the city. Read more… She had her hair shorn by a priest and thus consecrated herself to God for ever, becoming the foundress of the monastic life for women as Saint Antony the Great was its institutor for men. Being already embarked on the works of ascesis, she made rapid progress on the course which brings monastics to live a heavenly life here below, and she took the greatest care to keep her contests hidden from human sight lest she lose the final reward. She died daily to the world and to herself in order to live with Christ, and she rebutted with intelligence and discernment all the temptations insinuated by the demons. She raised herself constantly towards heaven by the holy virtues, and her renown spread round about her like a spiritual scent and attracted, despite herself, a growing number of fervent young women who came begging for her instruction and counsels for their salvation. At first, the Saint refused out of humility to break her silence, but she was constrained at last by charity to give way to their entreaties. With deep sighs, watered with tears, she revealed to them the treasures of wisdom and of knowledge that the Holy Spirit had set in her heart.

In the first place, Saint Syncletica reminded her disciples that charity — perfect love of God and neighbour — is the fulfilment of the divine Law in both the Old and the New Testaments (Ex. 20; Rom. 13:10), and that for those who withdraw from the world it must be the origin and aim of every action. ‘We shall be blessed’, she said, if we make as much effort to please God and to win heaven as people in the world do to heap up riches and corruptible goods.’ The delicate flower of holy charity blossoms only in a body and soul kept chaste and pure, not only from sins of the flesh and of the senses, but also from all connivance at the impure thoughts with which the Devil relentlessly assails warriors in the army of Christ. Hence they must always be on their guard, showing themselves as wise as serpents, in order to foil the devices of the enemy and, by their purity, they must be as simple as doves (Matt. 10:16). Just as clothes are washed and cleansed by treading them underfoot and turning them over and over, we should give ourselves up to poverty and to the ascetic life with the same expectation, joining vigilance, discernment, earnest prayer and holy humility to mortification of the flesh, in order that the soul, receiving the Holy Spirit, may become like a clean, white dove which rises up to God. The Saint herself had shown how to advance in humility — the basis of charity — by her hidden life, withdrawn from the world. ‘As treasure is seized and squandered by thieves as soon as it is discovered,’ she said, ‘so virtue fades and vanishes in the very moment that you make it known. Praise relaxes and enfeebles the soul like fire melting wax, while insults and scorn raise the soul to the height of virtue.’ She added an evocative comparison of the ascetic life with fire: ‘When you light a fire, at first the smoke makes your eyes sting and stream with tears, but soon after you enjoy the welcome warmth; in the same way, we have to kindle within us, through tears and sufferings, the fire of divine love, which Christ has promised to bring on the earth (Luke 12:49), in order to rejoice afterwards in the consolation of the Holy Spirit.’

The luminous teachings of the Saint filled the young women who listened to her with burning zeal; no longer willing to leave her, they desired to remain at her side day and night in order to contemplate in her person a living image of evangelic perfection. After resisting their pleas for some time, she resigned herself to the will of God, and guided her growing community along the narrow way to the Kingdom of Heaven, as one pilots a boat between reefs. She exhorted her disciples to adorn themselves with spiritual raiment in awaiting Christ with the same care as a bride devotes to preparing herself for an earthly union. She taught those who lived in community to prefer obedience and the casting away of their own opinions or judgements to feats of ascesis, and she exhorted them to encourage and to correct each other by word and, above all, by example in order to keep clear of the snares of the evil one — laxity on the one hand and vainglory on the other — because this is how to advance, with moderation and discernment, on the royal road of humility.

Although her body was weakened and withered by fasting, the soul of Syncletica was illumined by Christ, the Sun of Righteousness, and she shone brilliantly in her holy teaching, in her infallible discernment, before which all the illusions and machinations of the devil took flight, and above all in her constant progress towards perfection. In her latter years, to the free will offering of ascesis she added patience in illnesses, for she was put to the test by continual fevers and lung troubles, which like a file slowly wore down her body. When she reached the age of eighty-five, the devil put her to a final test, having obtained from God the power to submit her, for three and a half years, to sufferings such as righteous Job had endured for thirty-five years. While he attacked Job and the holy Martyrs from without, he struck at the Saint with the same savagery but from within, burning her entrails by a cancer as in a slow fire, which caused her excruciating pain. She bore these trials with patience and thanksgiving and even made use of them to instruct her disciples, saying, ‘If illness strikes us, let us not be distressed as though physical exhaustion could prevent us from singing God’s praises; for all these things are for our good and for the purification of our desires. Fasting and ascesis are enjoined on us only because of our appetites; so if illness has blunted their edge, there is no longer need for ascetic labours. To endure illness patiently and to send up hymns of thanksgiving to God is the greatest ascesis of all.’

The devil would not admit defeat, and he took away her power of speech, depriving her of the formidable weapon of her word; but, simply to see the serenity of the Saint’s countenance amid such great sufferings, replaced every other teaching and strengthened those who approached her in the love of God. He then attacked her body with gangrene, and the stench of putrefaction was so great that in order for her disciples to stay near her they had to fumigate the air with much perfume and to anoint her decaying limbs with sweet spices, as if for a corpse. But nothing could subdue this weak woman who had become, by the Grace of God, more valiant than any warrior. Scorning death and the impotent devices of the evil one, she was ministered to by the angels and was able to contemplate with joy the glory beyond all utterance of the light of Paradise. In this way, at the end of a three-month martyrdom, she departed to the Lord to receive the crown of her contests, after having predicted the day of her death and consoled her disciples in her last words to them.

Note: The wonderful biography of St Syncletica [of which we saw a summary], attributed to St Athanasius of Alexandria, is one of the basic texts of Orthodox spirituality.

Source: The Synaxarion: The lives of the Saints of the Orthodox Church, volume three (January-February), Holy Convent of the Annunciation of Our Lady, Ormylia, 2001 (pages 56-59).