Jerusalem Power

9 Απριλίου 2010

To spend the past few days in the crowded, narrow streets of Jerusalem’s Old City, among the multilingual throngs marking Passover or Easter, was to get an unforgettable sense of the power this place has over the minds of millions. It also gives an insight into some of the ways Jerusalem, and control of access to its holy sites, plays into global power politics.

For the majority of Palestinians who are Muslim, as well as for the Islamic world beyond, the Jewish state of Israel’s hold on the city since its capture from Jordan in the 1967 war is a deep grievance. Sporadic violence around the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa mosque has flared again this year.

But with the confluence this year of the Easter calendars of both Western and Eastern churches, as well as the Jewish Passover celebrations, it was the issue of Christian access and the competing claims of different Christian denominations to the holy sites of Jerusalem, that was particularly in focus this past week. And if it was American-accented English that dominated among the visiting Jewish families crowding towards prayers at the Western Wall and which served as a reminder of the powerful alliance Israel enjoys, despite current turbulence, with the United States, it was the Russian spoken by many of the Christian pilgrims which indicated one of the main trends changing the balance of power within that fractured religious community.

The Israeli state insists on its commitment to free access to the Old City for all religion. Complaints over Easter from the Palestinian Christian minority have been met by Israeli assurances that permission to enter Jerusalem is granted where possible and by pleas for understanding of security concerns in a city blighted by violence. There are also concerns about crowd control. Some Israelis also point out that, under Jordanian control from 1948 to 1967, Jews had virtually no access. Local Christians in the, predominantly Greek Orthodox, Christian Quarter and in the Armenian Quarter now complain however, like their neighbours in the Old City’s Muslim Quarter, of encroachment on territory by Jewish groups seeking property. Israel says its laws are fair to all. Some among the Old City’s Christian minority, notably clergy, complain of intimidation by Jewish radicals, including spitting on them in the street.

The treatment of minority Christians by Jerusalem’s rulers has long been an issue in diplomacy. In the 19th century, it was the Muslim Turks who found themselves on the receiving end of pressure from the Christian powers of Europe. Even today, codes regulating relations among the Christian denominations are the product of Ottoman attempts to appease international pressure or to keep the peace among the different churches competing for a slice of hallowed ground around the traditional tomb of Jesus.

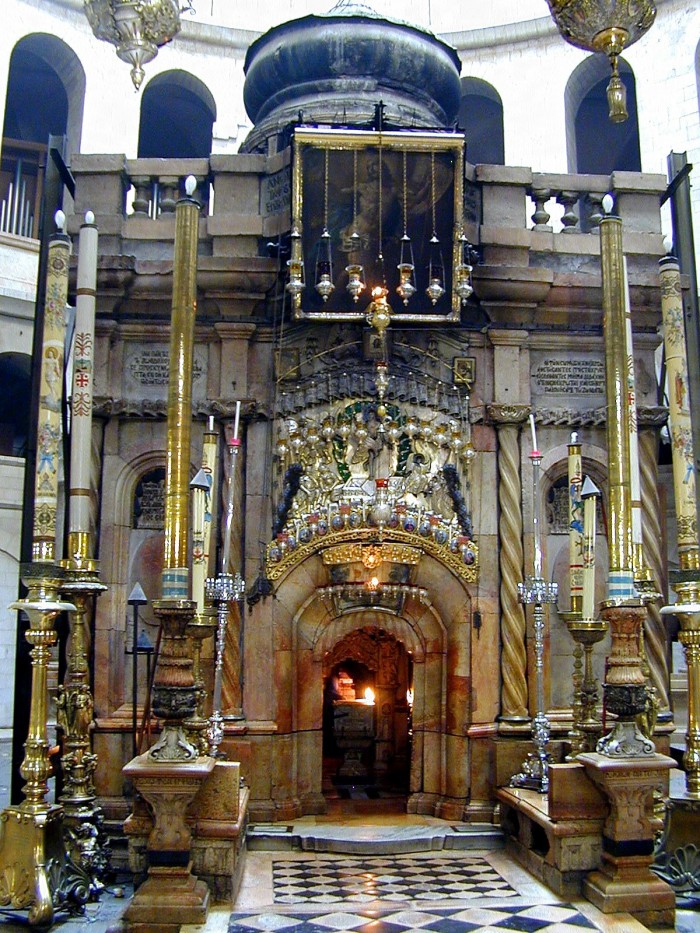

Standing amid the rumbustious and noisy sectarian jostling at the Holy Sepulchre on Easter Saturday, as the Eastern churches took part in the millennium-old ritual of the Holy Fire, it was this competition among the Christians that was most visible, and also the subject of plenty of conversation in the hours of waiting before the Greek Orthodox Patriarch, followed by a senior Armenian cleric, emerged from the tomb at the heart of the church bearing flaming torches symbolic of the resurrection. Essentially, local Armenians and Greek Orthodox worshipers were asking “Will the Russians take over?”

During the centuries of Ottoman control, as subjects of the sultan, the Greeks had favoured access to Jerusalem while Western churches were left out in the cold. Armenians, too, had insiders’ rights within the Ottoman empire. But as the sultans’ grip weakened, Roman Catholics and Protestants, backed by the rising European imperial powers, staked their claims in the city in the second half of the 19th century. Russia, repeatedly at war with the Turks during that time, was a relative latecomer, however.

And by the time Russia then abandoned Christianity after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, virtually simultaneous with the fall of Jerusalem to British forces and the collapse of the Ottoman empire, the “status quo” agreement that allocated rights over the Holy Sepulchre to the Greeks, Armenians and Catholics, with no role for the Russian church, remained in place. It has done so through the succeeding periods of British, Jordanian and, now, Israeli rule. But, today, with the huge upsurge in Russian religious observance since the fall of Communism two decades ago, and an intimate relationship between the Russian Orthodox Church and the state and economic power structures there, some in Jerusalem are wondering if that status quo can survive. The future balance of power among the Christians of the city, in terms of property rights and access to the Sepulchre and other key religious sites, could, as under the Ottomans, again be determined by the interests of the city’s, non-Christian, masters.

Those churches with international backing that can influence Israel may do better. The weakness of some denominations, like the Egyptian Copts, the Syriac church, Ethiopians and others, was demonstrated again on Saturday by their marginal roles at the Holy Fire ceremony (despite their noisy efforts to parade their clergy). Catholics, who with the Greeks and Armenians are the third power over the Holy Sepulchre but eschew the Holy Fire tradition, can count to some extent, like the Protestant churches, on the European Union and Americans to press their case with the Israeli government. The Greek Orthodox and Armenian churches, with perhaps the biggest shares to lose, have less certain international power behind them. The Greek state’s current economic woes were much cited this Easter as a reason for fewer Greek pilgrims.

And the Russians? Well, they have numbers on their side, both in terms of people and money. One Russian businessman standing near me in a prime spot in the Sepulchre church on Saturday confided to paying $700 for a pass from a member of one of the shrinking local Christian communities allocated some of the few thousand spaces for the Holy Fire ceremony. Thousands of Israeli police around the Old City, including dozens inside the church itself, ensured no one could take part without their permission.

Israel has a complex but essential diplomatic relationship with Moscow, which in Soviet days favoured its Arab enemies. And so it has plenty of reason to use what one Christian observer called a “free pass” — its control of access to Jerusalem and its holy sites — to secure diplomatic benefits, including from Russia. (Though control of occupied East Jerusalem, and especially the Old City and the holy sites, forms a core element of peace negotiations with the Palestinians, few see an early end to Israel’s gatekeeper role.) Israel is seeking Russian cooperation in a multitude of foreign policy spheres, not least in curbing a hostile Iran, to which Russia has hitherto been planning to provide armaments and nuclear technology. Among goodwill gestures to Moscow, the previous Israeli government moved to return a piece of prime real estate in west Jerusalem that once formed part of a major Russian Orthodox pilgrimage centre. And the most visible development of late, not least over Easter, has been the Russian influx on the streets. With a million citizens who are recent immigrants from the Soviet Union, including the foreign minister and tourism minister, Israel has seen the economic potential of those ties, notably in the form of mass Christian pilgrimage. It has scrapped visa requirements for Russians, who now form the the second-biggest contingent of visitors (after Americans) to Israel, a country for which tourism accounts for 6 percent of national income.

As one Armenian worshiper at the Holy Sepulchre put it on Saturday as he surveyed the massed ranks of pious Russians (and the not so pious, with their video cameras running): “The political stakes are rising because of this Russian involvement. In 20 years, we may see a change in the old ’status quo’ among the Christians.”

Source: http://blogs.reuters.com/axismundi/2010/04/05/jerusalem-power/