What is an Orthodox Woman? (2)

19 Μαρτίου 2010

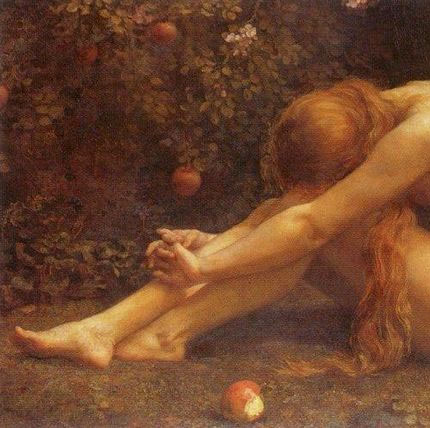

The next great epoch in the history of women is embodied by the one who has been

called the second Eve, as Christ is the second Adam: Mary, the Mother of God. As

it was given to a woman to exercise her free will to banish all humanity from

Paradise, so it was given to a woman to provide, by her own will, the means of

man’s restoration to his blessed state. Without Mary’s willing and complete

surrender to the will of God, there could have been no Incarnation, and thus no

crucifixion and no Resurrection—in other words, no Savior and no salvation for

mankind.

As Eve was the mother of all mankind, so it was through motherhood that Mary gave

this most precious gift to all humanity. Thus Mary became the Mother of all those who would become the children of God. In Mary we see the epitome of all

that redeemed woman can become— a state even more glorious than that Eve held

before her Fall. Consider some of the qualities that make Mary, the Mother of

God, the ultimate model around which our lives, even in this modern, frenetic

day and age. can and must be molded:

1) Mary willingly submitted to the will of God. Although she was

chosen, she was not forced: her obedience was voluntary and wholehearted. Later,

as Joseph’s wife, she also submitted willingly to her husband—she who had

known God more intimately than any other human being as she carried Him within

her womb.

2) Mary responded to God in faith. What was asked of her must

have been frightening and was certainly dangerous; but Mary trusted the love of God for her

protection.

3) Mary risked everything for motherhood. In her society, for a

young woman to become pregnant outside of marriage was the ultimate degradation.

Had Joseph been a hardhearted man, Mary could have become a complete pariah,

ostracized by her neighbors, unable to marry, with no means of supporting herself

and her child. How many women in our society have chosen abortion rather than

face circumstances less difficult than these? But Mary chose rather to risk her

own life to give life to another.

4) Mary took on the role of interceding for men and of leading them to Christ.

At the wedding at Cana, she first made known the people’s need to her Son,

knowing in spite of His protests that He would fill that need; then she said to

the people, “Whatever He says to you, do it” (John 2:5). She thereby exhorts

us all, her spiritual children, to respond to Christ with the same loving,

trusting obedience she herself showed.

Paul Evdokimov, in his book Woman and the Salvation of the World (St.

Vladimir’s Seminary Press. 1994), sums up the spiritual role (or “charism”)

of women, as exemplified by Mary, thus: to give birth to Christ in other people.

We may be called to physical motherhood, to pass on our faith to our children:

or we may be called to spiritual motherhood, to show forth the image of Christ

to all men and call them to Him.

WOMENIN THE CHURCH

Christ showed, through His own behavior to women and through His teaching to His

disciples, that while the place for proper headship and divinely established

authority remained a constant both in the home and in the Church, a significant

shift had occurred in the old order of male/female relationships which had

prevailed since the Fall. Christ treated women with dignity, respect, and compassion.

In His teaching on marriage (Matthew 19:3-9), He restored their marital rights

to what they had been “in the beginning,” before allowances had to be made

for the hardness of men’s hearts. Through the redemption accomplished by His

death and Resurrection, Christ made it possible for men and women once again to

strive for the ideal established in Paradise: a loving cooperation between

equals with different, complementary roles.

This ideal was largely upheld in the first few centuries of the Church. Women swelled

the ranks of the saints and martyrs, giving their lives to God in a variety of

roles, including those of prophetess, teacher, and deaconess as well as the more

traditional ones of wife, mother, and performer of charitable works. When men

began to seek the desert as a place to live out a more radical commitment to

God, women—beginning with Saint Mary of Egypt, to whose holiness even Saint

Anthony the Great deferred — were not far behind.

Within the family, the position of women was better among Christians than it had ever

been before. While Saint Paul exhorted wives to submit to their husbands—which

was nothing new—he also, even more strongly, exhorted men to love their wives

“as Christ also loved the church” (Ephesians 5:25)—in other words, to the

point of giving their lives for them. This was something new. The ancient

curse was beginning to crumble.

At the same time, however, there were teachers in the Church who held to a view of

women more in keeping with the views of their Jewish forebears (succinctly expressed

in the traditional male prayer, “Thank You, Lord, that You did not make me a

woman”). Some blamed women entirely for the Fall and claimed that they were

inherently evil, to be avoided by any man who would seek righteousness. Some

insisted that marriage and sexuality came into being only after the Fall and

were nothing but a necessary evil for the propagation of the species. One cannot

but suspect that these men—mostly celibates— were misplacing the blame for

their troublesome bodily passions, assigning that blame not to their own fallen

nature and the temptation of the devil, but to the unfortunate and inadvertent

object of those passions. woman.

As the centuries went by, this distorted view began to exert a greater influence

over the Church’s attitude toward and treatment of women. Women gradually came

to be excluded from the diaconate and from other ministries in which they had

previously taken an equal part with men. Women who achieved sanctity were

praised as having “overcome” their weak and evil feminine nature and become

as righteous as men.

Women never completely lost their champions, however. In the nineteenth century in

Russia, feminine spirituality began to come into its own again. Several notable

elders, including Saint Seraphim of Sarov and Saint Theophan the Recluse, made

it their business to encourage women, both in the world and in the monastic

life. Both of these men founded and directed women’s monasteries, and offered

spiritual direction to countless laywomen, in person or through correspondence.

These godly men had the prophetic insight that it would be primarily through

women that the Faith would be preserved in Russia during the seventy years of

communist persecution, and they wanted women to be prepared.

To be continued….