Be Like Children

14 Ιανουαρίου 2010

Alexander Schmemann Fr.

“Be like children” (Mt 18:3)–what can this mean? Is not our whole civilization focused on the task of turning children into adults, of making them as smart, as analytical, and as prosaic beings as we ourselves are? And are not all our discussions and arguments directed precisely at the adults for whom childhood is simply a time of development, of preparation, a time precisely for overcoming any childishness in oneself?

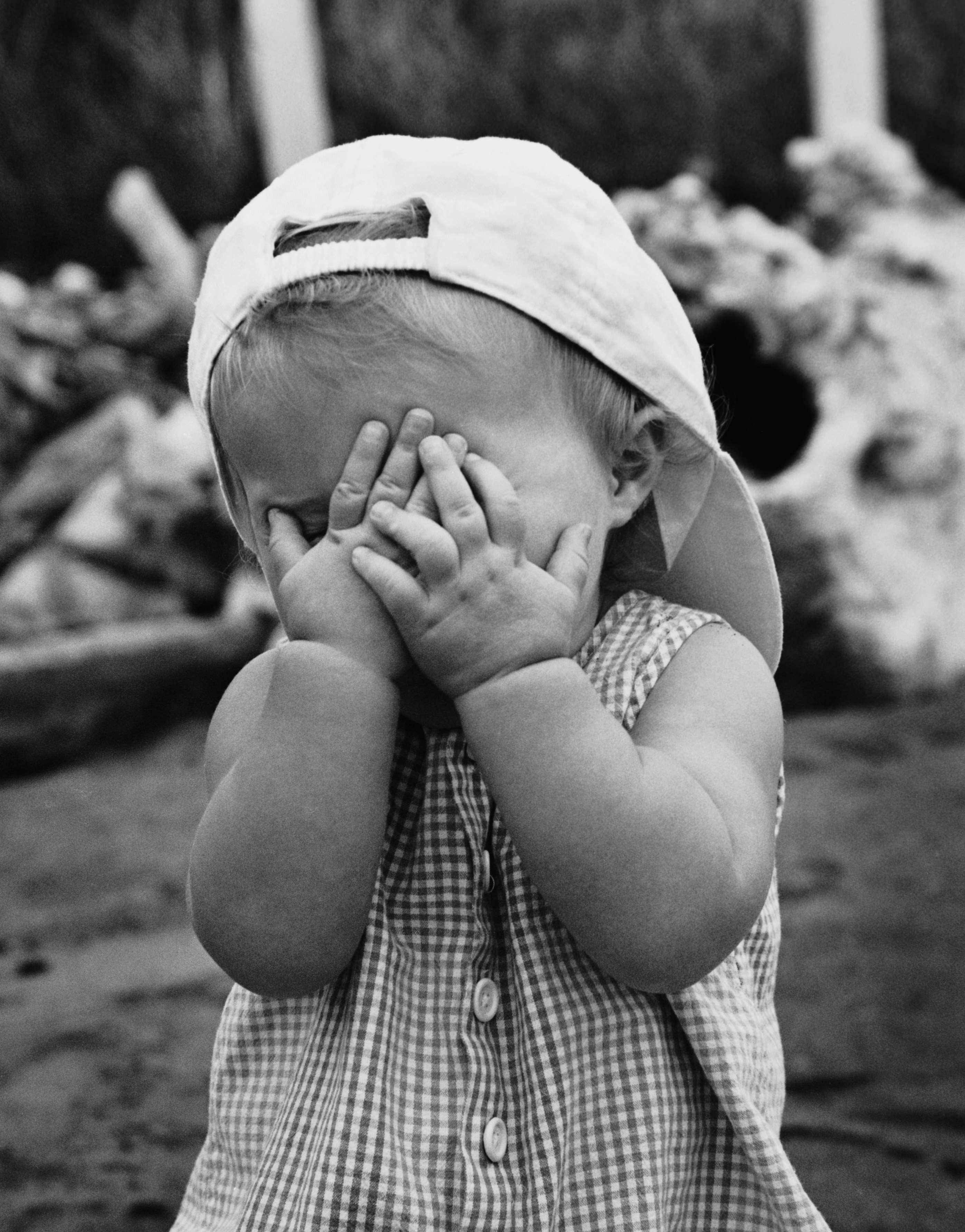

And yet, “Be like children,” says Christ, and also: “Do not hinder the children to come unto me” (Mt 19:14). And if this is said, then there is no reason to be ashamed of the unquestionable childlikeness that is connected with religion itself, and to every religious experience. It is not accidental that the first thing we see as we enter a church is the image of a child, the image of a young mother holding a child in her arms; and this is precisely what is most important in Christ–the Church is concerned with the fact that we should not forget this first and most important revelation of the divine in the world. For the same Church further affirms that Christ is God, Wisdom, Mind, Truth. But all of this is first of all revealed in the image of this child; it is precisely this revelation that is the key to everything else in religion.

What can they mean, these words: “Be like children”? Certainly these words cannot refer to some kind of artificial simplification, the denial of growing, of education, of having the experience of growth, of development–that is, all of which we call in childhood the preparation for life, the mental, emotional, and physical maturation. In the Gospel itself it is said about Christ that he “grew in wisdom” (Lk 2:40).

In addition, “Be like children” in no way signifies some sort of infantilism; it is not a supremacy of childhood over adulthood; it does not mean that in order to receive religion or religious experience one has to become a simpleton, or more crudely, an idiot. This is the understanding of religion by its opponents. They reduce it to fairy tales, to little stories and riddles, which only children or adult children–undeveloped people–can accept.

What is the meaning of the words of Christ? The question is not about what a person acquires in becoming an adult, for this is evident even without words, but about that which he loses, as he leaves his childhood. There is no doubt in the fact that he does lose something, something unique and precious, that for the rest of his life he remembers his childhood as a paradise lost, as a kind of golden dream, at the end of which life became sadder, emptier, fearsome.

I believe that if we had to define this in one word that word would be “wholeness.” A child does not yet know the fragmentation of life into past, present, and future, the sad experience of vanishing and irretrievable time. He is completely in the present; he is totally in the fullness of everything that is now, be it joy, be it grief. He is completely in joy, which is why people speak about “childlike” laughter and about a “childlike” smile; he can be completely in grief and sadness, and this is why we speak about the tears of a child, and thus, why a child so easily and unreservedly cries and laughs.

A child is whole not only in relation to time, but in relation to all of life; he gives himself to everything with his entire being; he does not understand the world by deliberation, through analysis, or through one of his particular emotions, but with his whole being without reservation-and this is why the world is open to him in all of its dimensions. If in his eyes the animals are speaking, the trees are suffering or rejoicing, the sun is smiling, and an empty matchbox can miraculously appear as a car, or a plane, or a house, or whatever, this is not because he is silly or immature, but because open and given to him at the highest level is this feeling of the miraculous depth and connectedness of everything with everything. He has the gift of full indwelling with the world and with life. And in growing up, we indeed hopelessly lose all of this.

First of all we lose this very wholeness. In our mind and consciousness the world disintegrates to its constituent parts, and outside of this profound interconnection all these elements become isolated, and in their isolation become limited, unidimensional, and boring.

We are beginning to understand more and more, but less and less to truly comprehend. We are beginning to acquire knowledge about everything, but no longer have a real communion with anything.

But this miraculous connection of everything with everything, this possibility of seeing the other in everything, this possibility of a full giving of oneself and connectedness, this inner openness, this trust in everything, is precisely the very content of religious experience-this is in fact the feeling of divine depth, of divine beauty, of the divine essence of everything, this is in fact the direct experience of God, who is all in all!

The very word “religion” in Latin means “connection.” Religion is not simply one area of experience; it is not one category of knowledge or experience; religion is the connection of everything with everything, which is why, in the final analysis, it is the truth about everything. Religion is the depth of things and their height; religion is light, which flows from everything, thereby illuminating everything; religion is the experience of the presence in everything, behind everything, and above everything, of the final reality, without which nothing has any meaning. And this whole divine reality can only be perceived with an understanding that is whole, and this is the meaning of “Be like children.”

It is to this that Christ calls us when he says “The one who does not receive the kingdom of God like a child, will not enter it” (Mk 10:15). For in order to see, to desire, to feel, to receive the kingdom of God it is necessary precisely to see this depth of things, to see that which in the better moments of our life they proclaim to us, that light which begins to flow from them when we return to our childhood wholeness