On the Role of Women in the Church

31 Δεκεμβρίου 2009

A transcript of a talk given at St. Tikhon of Zadonsk Orthodox Retreat on 7 September 2009 in Guerneville, CA

The issue of women in the Church has been raised many times during the history of Christianity, beginning with the very first decades of the Church’s existence. That is why, when in the twenty-first century one asks about the role of women in the Church, one does not speak of this role—Christ Himself spoke about it and the Apostle Paul wrote about it in his letters—but the continuing problem of the relationship between genders in the family, society, and the Church. In Church consciousness, this problem is usually expressed in terms of bearded men in black possessing administrative authority which they withhold from women, even if the latter choose to glue on a mustache and don a black robe. From the point of view of modern Western culture—to which not only immigrants making their lives in the United States belong, but also in a significant way Orthodox people living in the European part of Russia—there is clear evidence of the discrimination of the Church against women only because they were born women. This is why it seems somewhat strange to me that I, a bearded man in a black robe who possess some limited administrative authority in my parish—a small part of the Church, have been invited to tell women about their place in the Church.

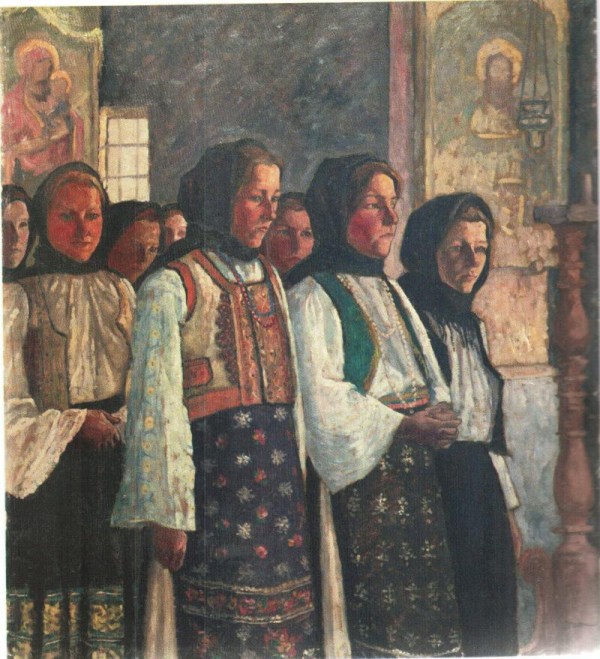

Well, in my opinion, the woman’s place in a church is on the left; that is to say, on the side where the icon of the Theotokos is found on the iconostasis. It must be noted that this placement gives more honor to women than it does to men. Practically, when the priest prays as one of us—facing the east—then men stand on his right, but when Christ Himself comes to us from the royal doors—whether in a blessing or in the Holy Gifts—then it is the women who end up on His right hand. Thus, if we were to imagine Christ Who stands in the royal doors and separates His sheep from goats (Matt. 25:32), then it is the women who end up on His right, but the men—on His left (33).

Of course, all of this has been said only in a half-joking manner. The issue of the interrelationship between genders in the Church is complex, that is to say, it consists of several parts. Let us take a closer look at some of them.

Introduction: A Few Notes on Society and the Church

It is no secret that society, with its philosophy, ideology, and culture has a great influence on Christian thought. Preaching the Gospel in the Hellenistic world, the Church used terminology and methodology that could be understood by Hellenistic society; existing within the boundaries of the Roman Empire, the Church expressed its theology through political and legal imagery and allegories; having faced Soviet persecution, the Church was forced to look for ways to survive; and living in a modern materialistic society, the Church enters into a polemic with it, exposing its spiritual bankruptcy.

On the other hand, the Church consists not only of our heavenly patrons, but also of us, quite earthly people, who are influenced by our upbringing, ideology, propaganda, various fads, fallacies, and trendy philosophies. We not only take something from the Church, but also bring something to the Church, into its life and worldview. This is not always bad. Imagine that when you were three years old you were told that your life experience was complete, that from that point on you must learn only from examples found in the lives of previous generations, and that your own thoughts, feelings, and experiences must be either treated with suspicion or rejected altogether. As absurd as this sounds when applied to a person, it would be equally absurd to apply such as standard to the Church, as if preserving it somewhere in the fourth or fifth century, like a jar of pickles.

However, we must remember that our personal feelings cannot always be a measure of all things, and that it makes sense to reinvent a wheel only after we have familiarized ourselves with already existing models, but not sooner. I think it was Fr. Deacon (now Protodeacon) Andrei Kuraev who once offered the following example. We would never think of telling a neurosurgeon how to operate on a human brain or a pilot of a jetliner which button to push. Why then do we not think twice before doubting the wisdom of those who have been leading the Church on the path of sanctity for the last two millennia?

It is easy to understand that some of the charges brought up against the Church stem from a misunderstanding of the goals that Christ has set for his Bride. For example, establishing gender equality is not the purpose of the Church. This does not at all mean that the Church cannot occupy a certain position with respect to discrimination, inequality, or slavery. However, rooting out earthly slavery is not a direct task of the Church, which is charged with proclaiming Christ’s victory over the slavery of sin; and both men and women, slave and free (Gal. 3:28), white and black can equally partake of this victory.

The Church has always perfectly and consistently preached the Good News that it received from the Lord Himself: “to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed” (Luke 4:18). But this does not mean that every member of the Church—even from among the hierarchy—has always followed the spirit and letter of the Gospel. Our close ties with the earthly all too often reveal themselves in our relationship with the heavenly. Desiring earthly goods for ourselves, we imagine that Christ is an earthly king, forgetting that His kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). Striving for earthly authority, we turn Christ into some kind of a tyrant, forgetting that He came to serve, not to be served (Mark 10:45). Finally, trying to trample down a wife who “raised her voice” (Luke 11:27), we like to cite the words “let the wife see that she respects her husband” (Eph. 5:33), and shy away from “husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (25). It is not the fault of the Church if we prefer such perverted “theology,” rather, it is the fault of our sinful nature. Certainly, there are such treatises written by the clergy as “Domostroi,” but they do not reflect the Christian view on the roles of men and women as much as they comment on the contemporary situation of the society. By the way, the author of “Domostroi” consciously tried to soften contemporary morals by pointing out to the barbarians the principles of Christian love. In other words, such treatises present more of a socio-historical interest than serve as a standard of Christian relations between a husband and a wife.

But the most striking is not the fact that a seal of our sinfulness can be found on various works by the clergy, but that even the Sacred Scripture must allow for our hard-heartedness. A surprising example of this can be found in the dialogue between Christ and Pharisees: “Why then did Moses command…—For your hardness of heart Moses allowed you… but from the beginning it was not so… And I say to you…” (Matt. 19:7-9). Thus, we must be very careful when citing the Scripture, and not look at the divine revelation through the prism of our hard-heartedness, but through the loving eyes of the Source of this revelation.

Women in the Church

Orthodoxy does not have a gender problem, as there is no question about the role of women in the Church. Such problems and questions are brought into the Church from society and family by people who live in the society and family. Bickering with his wife, for example, a man may throw at her a citation from an epistle of the Apostle Paul, an act that will surely be reflected on both his and her Christian self-awareness. Having watched feminist warnings of discrimination on television, a person may consciously or unconsciously bring them into the Church and begin to compare the life of the Church—at least as he or she sees it—with humanist and feminist principles. Additionally, the problem can be worsened by some clergy who—some jokingly, some not—cite from the Fathers something like: “Stay away from women and bishops,” forgetting to disclose that this advice was given by a particular elder to a particular novice and does not represent the worldview of the Church.

Of course, we may wonder whether there is such a thing as scholastic or abstract Orthodoxy. Most likely, we will be compelled to say that such Orthodoxy does not exist, just as a scholastically-abstract unhypostasized human cannot exist. As my painfully-famous compatriot Vladimir Lenin once wrote: “There is no abstract truth; truth is always concrete.” [1] This, however, does not mean that we cannot examine the foundational principles of the Orthodox faith which are true always, everywhere and for everyone. And it is in the principles of the Orthodox faith that we do not find a gender problem. Unlike some other faiths such as Hinduism[2] or certain Islamic sects,[3] Orthodoxy teaches absolute equality of people in their relationship to God, salvation, and eternal life, regardless of their gender, nationality, social status, etc.

“There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28). This, of course, does not mean that Paul no longer considered himself a Jew, a freeman, and a male, but rather some sort of transnational, genderless, and undefined creature. Quite the opposite—the Apostle understood and accepted the reality of this earthly life. But the life of a Christian, just as the life of Christ Himself, is the union of that which cannot be united: the earthly and the heavenly, the temporal and the eternal, the dust and the breath of life (Gen. 2:7)—a union, not a rejection of one in favor of the other. The purpose of Christian life as Orthodoxy sees it is theosis, that is to say, the theosis of our entire being: “…enter Thou into my members, into all my joints, my reins, my heart” (from Prayers of Thanksgiving following the Holy Communion, Prayer 3). Christ came to make the whole man well (see John 7:23)—not to kill the body and free the soul, as if from a cage. And the resurrection is not a resurrection of souls only, but also of bodies. Finally, it is our temporal earthly life that determines the trajectory that leads into eternity; and it was Christ’s earthly life—with His incarnation, service, crucifixion, and resurrection—that brought salvation to the world.

This is why we can find two elements: the heavenly and the earthly in the way that the Church relates to each person. The heavenly angelic element is manifest in the fact that in a church all stand equally before God, all equally participate in the service of the Divine Liturgy, prayer rules are the same for everyone, all equally partake of the Body and Blood of Christ, the fasts are the same for all, and in all matters of salvation and theosis Orthodoxy does not know any differences between men and women.

However, the earthly element is also present in the Church. For example, the Church sanctifies marriages only between a man and a woman, thus acknowledging this essential distinction among people. Note that Christian marriage is not a toll to be paid to our sinful nature or some unnatural encroachment of the socio-biological element on the life of the Church, but quite the opposite—the restoration and sanctification by the Church of the institution established by the Creator before the fall of Adam and Eve (Gen. 1:27-28; 2:22).

Therefore, insisting on the equality of people, the Church also insists on their uniqueness. Remembering that every person in an hypostasized nature, the unity of nature and the uniqueness of hypostases can be shown on the example of the Holy Trinity. Each Person of the Trinity possesses one and the same divine nature, but is different and unique in His hypostasis: the Father gives birth, the Son is born, the Spirit proceeds; the Father is not the Son or the Spirit, the Son is not the Father or the Spirit, the Spirit is not the Father or the Son. The hierarchy within the Trinity is established through the relationship of the Persons of the Trinity, that is to say, through love, rather than through some supremacy of the nature of the hypostasis of the Father over nature or the hypostases of the Son and the Spirit. Examine, for example, St. Andrei Rublev’s icon “The Trinity”: while the Father is depicted at the head of the table,[4] all three Persons of the Holy Trinity take part in the pre-eternal council, and it is the Son Who is making the decision.

In the same way, in the way the Church relates to men and women we may sometimes observe a certain “primacy of honor” of men, while maintaining the absolute equality of male and female hypostases and the unity of nature. However, more honorable than not only men but even the cherubim is a woman—the Most Holy Theotokos, whom Orthodoxy, unlike Roman Catholicism, considers to be like us in every way and in everything, except personal sin. Sometimes, this “primacy of honor” of men is cited as the reason for the impossibility of female priesthood in the Orthodox Church. But it would be incorrect to think that only men can be priests in the Church.

The fact is that according to the Apostle Peter, priesthood belongs to all Christians without exception: “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people…” (1 Peter 2:9) That is to say, a priest standing at the Holy Table does not possess and cannot possess anything that the whole Church does not already possess. Outside of the Church there cannot be priesthood, because priesthood is the inherent quality of God’s people. This quality or, more correctly, this grace is as if guided toward and focused upon the person of a bishop and through him a priest, but it is not a unique quality of just these persons, but rather of Christ and His Body—the Church.

Priesthood is possessed by the Church as the Body of the High Priest Christ. In some ways it can be said that priesthood is the relationship between Christ and His Church. Let us recall what it is that a priest does—he offers and accepts a sacrifice: “Sacrifice, master.—Sacrificed is the Lamb of God, that taketh away the sin of the world…”[5] But Christ’s sacrifice is offered for all of us, and all Christians accept it and in turn give themselves to Christ, offer themselves as a sacrifice to their God. Apostle Paul writes: “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me…” (Gal. 2:20) Thus, priesthood is not something inaccessible to women, but rather it is their inherent Christian calling. The Liturgy (Gr.—“common work”) is the service of the whole Church, and a priest by himself cannot serve the Liturgy.[6] Unlike in a synagogue, where a quorum of ten men is necessary for a public service,[7] in Christianity it is two or three gathered in Christ’s name—regardless of the worshipers’ gender.

As far as the priest’s stole is concerned, we do not know why Christ chose to be incarnate in a male body, but it was so, and all of the apostles were men, and from the first days of the Christian Church the obedience of priesthood has been given only to men, and even then only to some of them. This did not happen due to some socio-historical reasons—Christians broke quite a few of the ancient social norms; nor was it because the ancient world did not have women-priestesses—for it certainly had plenty. Apparently, it was pleasing to the Holy Spirit and the apostles that the institute of male priesthood be established in the Church. I must admit that in addition to that which has been said, I do not have a more definite answer to the question “why?” But some theological opinions exist which may be interesting.

Since a detailed theological treatment of the mystery of creation is not the topic of this paper, I shall point out only a few broad themes. Perhaps some may find it novel, but the first divinely ordained order of relationships between men and women can be referred to as “matriarchate”: “…a man leaves his father and his mother and cleaves to his wife…” (Gen. 2:24) Noting that the first man did not have a mother and father but only his Creator-God, we may understand these words as establishing a social order for future generations. In other words, if John Smith and Mary Jones decide to become “one flesh” (ibid.), then John must leave his family (mother and father) and cleave to that of his wife, that is to say, he must become John Jones. Nonetheless, the dynamic of the relationship between a man and a woman was not supposed to include elements of lordship or primacy.

In reality, things turned out to be different. Eve not only disobeyed God’s commandment and not only made a unilateral decision to become “like God” (Gen. 3:5), but then she fed[8] Adam after she had eaten, thus establishing her primacy over him.

Considering the punishment that followed after the fall, we must remember that God is not a vengeful torturer Who remembers wrongs, but rather a loving and merciful Physician Who willed to be tortured and crucified for our healing and salvation. Therefore, God’s punishment must be understood not as deserved torture, but rather as medicine. And by the type of prescribed medicine we can sometimes guess at the nature of the illness. “To the woman [God] said, ‘…your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you’” (Gen. 3:16). Perhaps, in the very sin that plagued Eve there was an element which is cured through obedience to her husband. And maybe this is why the Church has traditionally placed the burden of priesthood upon men and not women. Certainly, there can be other interpretations of these verses in the Scripture.

However, it must be repeated that no interpretation of Scripture changes the fact that the role of women in the Church is the same as the role of men—theosis. Why then are only men allowed in the altar? This is also not true. Actually, only clergy are allowed in the altar. The sixty-ninth canon of the Sixth Ecumenical Council forbids all laity—men or women—from entering the altar. The modern custom of letting non-clergy boys serve in the altar speaks of the lack of clergy, rather than of some privileged treatment of boys. Girls can also serve as acolytes in the altar until they turn twelve, in other words, until they enter the age of sexual maturity and menstrual bleeding that is associated with it. In the same way older women can receive a blessing to enter the altar. Although these practices are rare in most parishes, they do exist.

Finally, the last topic that should be discussed is the role of women in the family. The Apostle Paul likens the sacrament of marriage to the sacrament of Christ and His Church. Thus, examining the Orthodox understanding of marriage may help us to better understand the role of women in the Church.

Women in the Family

The most common opinion about the relationship between men and women is based—and for a good reason—on the texts from the Scripture read aloud during the wedding service. As was mentioned earlier, a one-sided understanding of the verse about wives being subject to their husbands (Eph. 5:22) often draws applause from the male crowd, but let us try to examine the true meaning of what the Apostle writes. Might it be that the Apostle Paul is more spiritual than we are, and that our comprehension of the mystery of Christ and His Church is no more insightful than that of the ancient Jews who wagged their heads unable to comprehend the mystery of our salvation (Matt. 27: 39:43)? Writing about women’s subjugation to their husbands, the Apostle Paul bases this principle on the parallel of the husband being the head of his wife in the same way that Christ is the head of His Church (Eph. 5:23). But what kind of headship is this? Is it the same as we observe among some “zealots” for piety? Let us refer to the relevant verses from the Scripture.

“For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government will be upon his shoulder…” (Isa. 9:6) What is “the government upon shoulders”? Is it some kind of epaulettes or shoulder boards—the usual symbols of government? Not quite. He was “bearing his own cross” (John 19:17), “He bore the sin of many” (Isa. 53:12). Is this the image of a general in epaulettes?—“He had no form or comeliness that we should look at Him, and no beauty that we should desire Him. He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces He was despised, and we esteemed Him not” (Isa. 53:2, 3).

A secular leader acts on the following principle: “Come to me, all ye to whom I have not yet ordered anything, and I will give you duties.” Christ says: “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matt. 11:28).

Who is the greatest in a secular kingdom?—He whose hat is the tallest and servants are many. But when Christ was asked who was the greatest in the kingdom of heaven, “calling to him a child, he put him in the midst of them…” (Matt. 18:1, 2).

“And he sat down and called the twelve; and he said to them, ‘If anyone would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all’” (Mark 9:35).

“If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet” (John 13:14).

Verses such as these are plentiful; all of them point to a very important quality of Christ’s headship—it is quite different from that of secular rulers and leaders. That is why the headship of a husband can have secular or heavenly qualities. These qualities are not mutually exclusive and can coexist in the same relationship. But without Christ’s kenosis, without His “emptying” Himself, there cannot be a Christian marriage, and all that is left is a socio-financial relationship.

Of course, the bearing of one’s cross does not apply to men only, as it does not apply to Christ only. The way of the Church and the way of each one of the spouses in a Christian marriage lies through self-denial: “If any man would come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow Me” (Matt. 16:24). Let us see how the Apostle Paul treats the issue of headship in a marital relationship: “Do not refuse one another except perhaps by agreement” (1 Cor. 7:5). That is to say, not by “the will of man” (John 1:13), or by the will of “the contentious and fretful woman” (Prov. 21:19), but “by agreement” (εκ συμφωνου).

Although we call ourselves slaves and servants of Christ, He calls us His friends (John 15:15) and lays down His life for us (13). This means that our slavery is not that of a captive who is bound by violence, but that of a loving heart which is captured by Christ’s love. In other words, the obedience of a wife who biblically refers to her husband as “lord” must be the free obedience of love. This may seem like an unattainable ideal, but was it not to us that Christ said: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Matt. 5:48)?

Conclusion

The role of women in the Church is the same as the role of every Christian regardless of gender, nationality, social status, health, etc.—collaboration with Christ in the task of our salvation (1 Cor. 3:9). According to her individual gifts, a woman can choose to serve the Church as an administrator, a theologian, an iconographer, or a choir director, pursue sanctity on a monastic path, or as a mother—but all these are merely outward expressions of some of the aspects of Christian life. The most important is “the hidden person of the heart with the imperishable jewel of a gentle and quiet spirit, which in God’s sight is very precious” (1 Peter 3:4). This is because the Body of Christ does not consist of administrators, theologians, or iconographers, not even of clergy, but of Christians. And the role of each Christian—man or woman—according to Saint Seraphim of Sarov, is the “acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God.”

[1] From the work “Chto delat?” (“What to do?”) (1902)—an apparent paraphrase of Hegel’s “If truth is abstract, then it is not truth” from Lectures on the history of Philosophy (“Introduction,” 1816). [2] In Hinduism, women occupy a lower position on the ladder of reincarnations than men do. [3] It must be noted that, despite quite obvious discrimination against women in many Islamic societies, the Quran insists that men and women are equal before Allah, and the law of Sharia prescribes equal punishments for crimes committed by men or women. [4] Not to be confused with the center of composition. [5] From the dialogue between a deacon and a priest during the service of Prothesis. [6] Except for isolated instances when due to special circumstances a bishop may authorize a priest to serve alone. [7] Minyan—in traditional Judaism is a quorum of ten men necessary for public worship. [8] Of course, here we must look at the religious aspect of the fall, and not at the fact that Eve fed Adam a supper of stolen apples.Source: http://frsergei.wordpress.com/2009/11/13/on-the-role-of-women-in-the-church-2/