Abortion and the Culture Wars: A Struggle Between Incompatible Views of Morality and Reality

5 Νοεμβρίου 2009

Herman T. Engelhardt*

I. Introduction: Understanding the Evil of Abortion

Abortion is a kind of murder practiced throughout the world, usually without a sense of guilt. It has become a widely-accepted medical practice supported by numerous governments and non-governmental organizations. The number of unborn children killed in their mother’s womb across the world is more than the entire population of Ireland, Greece, Hungary, Canada, Romania, Poland, or Spain. It may even be equivalent to killing the entire population of France annually.[1] Abortion has become particularly widespread in Eastern Europe, where the previous atheist-communist regimes brutally disrupted and dismantled Orthodox Christian culture and institutions.

In Eastern Europe in the late 1990’s, there were close to 75 abortions per 1000 women in the age range from 15 to 44, as compared to less than 20 abortions per 1000 in the rest of Europe. Of all pregnancies, in Russia 57% ended with abortion, in the Ukraine 53%, in Belarus 52%, in Romania 47%, compared to 13% in Spain.[2] In Greece about 11% of all pregnancies end in abortion, compared with about one in four in the United States.[3] Abortion’s widespread use is a special shame for countries whose cultural inheritance is predominantly Orthodox.

In Eastern Europe in the late 1990’s, there were close to 75 abortions per 1000 women in the age range from 15 to 44, as compared to less than 20 abortions per 1000 in the rest of Europe. Of all pregnancies, in Russia 57% ended with abortion, in the Ukraine 53%, in Belarus 52%, in Romania 47%, compared to 13% in Spain.[2] In Greece about 11% of all pregnancies end in abortion, compared with about one in four in the United States.[3] Abortion’s widespread use is a special shame for countries whose cultural inheritance is predominantly Orthodox.

This slaughter is very evil, but there is an element worse than the homicides themselves. There is a systematic, culturally grounded failure to grasp, much less acknowledge, the evil of abortion. It is impossible to account for the  widespread use of abortion apart from the character and significance of the secular culture within which it occurs. Acting immorally, acting sinfully, is surely wrong. But that wrongness has a remedy at hand, as long as the evil is acknowledged. The thief on the cross starts his journey to repentance and salvation when he confronts the truth, “we are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve” (Luke 23:40). The striking feature of the contemporary culture is precisely its shamelessness. The recognition of the evil of abortion is absent from the emerging, dominant, secular, global culture. This culture now constitutes a robust counter-culture to Christian culture, engendering a conflict between two incompatible understandings of reality and morality. This culture is intent on transforming social institutions throughout Europe and North America. A remedy for these circumstances can only be found in a profound change of heart and mind, an opening up once again to the full significance of the human good and human flourishing: the existence of God and the substance of the Christian life. A treatment for the crisis of abortion lies in recovering a proper view of human sexuality, reproduction, and flourishing, a view at loggerheads with the secular culture: Orthodox Christianity.

widespread use of abortion apart from the character and significance of the secular culture within which it occurs. Acting immorally, acting sinfully, is surely wrong. But that wrongness has a remedy at hand, as long as the evil is acknowledged. The thief on the cross starts his journey to repentance and salvation when he confronts the truth, “we are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve” (Luke 23:40). The striking feature of the contemporary culture is precisely its shamelessness. The recognition of the evil of abortion is absent from the emerging, dominant, secular, global culture. This culture now constitutes a robust counter-culture to Christian culture, engendering a conflict between two incompatible understandings of reality and morality. This culture is intent on transforming social institutions throughout Europe and North America. A remedy for these circumstances can only be found in a profound change of heart and mind, an opening up once again to the full significance of the human good and human flourishing: the existence of God and the substance of the Christian life. A treatment for the crisis of abortion lies in recovering a proper view of human sexuality, reproduction, and flourishing, a view at loggerheads with the secular culture: Orthodox Christianity.

II. Sin in the Ruins of Christendom

II. Sin in the Ruins of Christendom

A traditional Christian asks, “How can there be such a widespread acceptance of abortion? Why do people so readily use abortion, and with so little acknowledgement of guilt?” This is a puzzle, because authentic Christianity recognizes that

(1) all reality and history have deep meaning: all cosmic and human history goes from the Creation through the Incarnation and the Redemption to Final Judgment, so that within this context no pregnancy and no suffering borne is without enduring significance.

(2) All human interests, concerns, and accounts of human flourishing must be placed in terms of the pursuit of the holy, so that any costs and burdens one is obliged to bear have their final significance only in relationship to God.

(3) All human sexuality is set within the pursuit of salvation, so that all sexual activity and reproduction must be placed within the marriage of a man and a woman who offer their sexuality and procreation to God.

In terms of this insight into the deep meaning of reality, the human good, and human flourishing, choices regarding human sexual activity and reproduction, including abortion, are appreciated in their full significance in a way impossible in a secular culture, because all choices are located within a recognition of the existence of God, Who as a personal Creator frames the meaning of all created being. All created beings, including good and right actions, are like stars in a galaxy revolving around an immense central black hole. Though the life of the black hole is very different from, and governed by laws other than, those of the rest of the galaxy, none of the motion of the stars can be appreciated without reference to its massive presence.[4] Once a culture loses sight of God, all becomes foundationally disoriented.

In contrast, the secular culture attempts to locate all of human life, interests, and goals within the horizon of the finite and the immanent. Its appreciation of harms, benefits, and obligations, therefore, is short-term (i.e., it fails to recognize that humans are destined for eternity) and systematically incomplete. Sexuality, marriage, and reproduction are set within a robust collage of individually oriented concerns that are a function of a secular, post-Christian culture, which treats

In contrast, the secular culture attempts to locate all of human life, interests, and goals within the horizon of the finite and the immanent. Its appreciation of harms, benefits, and obligations, therefore, is short-term (i.e., it fails to recognize that humans are destined for eternity) and systematically incomplete. Sexuality, marriage, and reproduction are set within a robust collage of individually oriented concerns that are a function of a secular, post-Christian culture, which treats

(1) all of reality and history as of no ultimate significance: the cosmos is regarded as coming from nowhere, going to nowhere, and for no purpose.

(2) All human interests, concerns, and accounts of human flourishing are therefore accepted to be what humans as persons make of them.

(3) As a result, all human sexuality is set within the secular calculation of immanent costs and benefits.

This involves a position similar to that taken by the Sophist Protagoras (460-377 B.C.), who argued that all moral truth, indeed all reality, should be interpreted from the perspective of humans. When one is blind to the existence of the divine, human persons become the measure of all morality.

The result is a profound deformation of the appreciation of sexuality and marriage. A symptom of these changes is the radical dying out of European populations, as well as its ready acceptance of abortion. Europeans tend to avoid becoming pregnant, and when they do become pregnant, they often kill the child in the womb, thinking all the while that they have acted responsibly. Children demand self-sacrifice from their parents, and the more children, the greater the sacrifice. In addition, the greater the burden of a pregnancy, the more tempting it becomes to kill the unborn child and escape the responsibilities of parenthood. In particular, it is widely affirmed by the secular culture that a pregnancy in one’s teenage years and early twenties may jeopardize educational and career plans and is therefore a burden that need not be borne. The secularized, post-traditional culture accepts abortion (1)because of the burden of an unwanted child, (2) because the mother did not consent to the pregnancy, or (3) because the child in the womb suffers a serious physical defect. Unborn children become disposable.

The very availability of abortion becomes a kind of insurance against the burdens and disruptions of an unwanted pregnancy, protecting the priority that secular life-styles give to work, career, self-realization, self-satisfaction, and success understood within the horizon of the immanent. In this context the secular culture affirms the freedom to choose abortion as integral to human liberty and dignity,[5] in the process losing the ability to appreciate the evil of abortion and even the evil of infanticide.[6] Those who are comfortably nested within the emerging, dominant, secular, global culture perversely deem it evil to preclude abortion’s availability, because the lack of easy access to abortion brings into question well-established secular life-styles. Many therefore protest if physicians in national health services refuse to provide or even refer for abortion (or provide or refer for prenatal diagnosis in contemplation of a possible abortion). In this secular culture, it will seem improper if physicians in obstetrics and gynecology residencies refuse to be involved in learning abortion procedures. The defenders of secular culture seek to change the ethos of physicians and national health care systems by corrupting the consciences of physicians, nurses, and health care students. Any threat to the widespread availability of abortion is perversely considered immoral, as a coercive attempt to impose or enforce pregnancies. The availability of abortion is regarded in positive terms as an element of responsible reproduction, as well as integral to a false sense of liberty, equality, and human dignity – an ethos that has no place for the radical obligation given by Christ. “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Mark 8:34). The secular culture has institutionalized a radical inversion of values.

The very availability of abortion becomes a kind of insurance against the burdens and disruptions of an unwanted pregnancy, protecting the priority that secular life-styles give to work, career, self-realization, self-satisfaction, and success understood within the horizon of the immanent. In this context the secular culture affirms the freedom to choose abortion as integral to human liberty and dignity,[5] in the process losing the ability to appreciate the evil of abortion and even the evil of infanticide.[6] Those who are comfortably nested within the emerging, dominant, secular, global culture perversely deem it evil to preclude abortion’s availability, because the lack of easy access to abortion brings into question well-established secular life-styles. Many therefore protest if physicians in national health services refuse to provide or even refer for abortion (or provide or refer for prenatal diagnosis in contemplation of a possible abortion). In this secular culture, it will seem improper if physicians in obstetrics and gynecology residencies refuse to be involved in learning abortion procedures. The defenders of secular culture seek to change the ethos of physicians and national health care systems by corrupting the consciences of physicians, nurses, and health care students. Any threat to the widespread availability of abortion is perversely considered immoral, as a coercive attempt to impose or enforce pregnancies. The availability of abortion is regarded in positive terms as an element of responsible reproduction, as well as integral to a false sense of liberty, equality, and human dignity – an ethos that has no place for the radical obligation given by Christ. “If anyone would come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Mark 8:34). The secular culture has institutionalized a radical inversion of values.

III. Abortion: Condemned from the Age of the Apostles and the Fathers

III. Abortion: Condemned from the Age of the Apostles and the Fathers

From the time of the Apostles, Christianity recognized that abortion is incompatible with rightly turning to God. The earliest writings portraying the Christian life address the issue of abortion. For example, in the Didache, a work composed between A.D. 50 and 70 (which, among other things, shows that Christians have fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays from the time of the Apostles), one finds abortion listed among the very serious sins. “Thou shalt do no murder; thou shalt not commit adultery; thou shalt not commit sodomy; thou shalt not commit fornication; thou shalt not steal; thou shalt not use magic; thou shalt not use philters[7]; thou shalt not procure abortion, nor commit infanticide.”[8] A similar set of prohibitions, including a prohibition of abortion, is also found in the 1st- or 2nd-century Epistle of Barnabas. “Thou shalt not commit fornication, thou shalt not commit adultery, thou shalt not commit sodomy… Thou shalt not procure abortion, thou shalt not commit infanticide.”[9] Abortion has always been condemned by Christianity.

This condemnation of abortion by Christians continues unbroken. The 2nd and 3rd centuries are replete with Christian statements against abortion. Septimus Tertullian (A.D. 160-240), for example, stressed that “with us, murder is forbidden once for all. We are not permitted to destroy even the fetus in the womb, as long as blood is still being drawn to form a human being. To prevent the birth of a child is a quicker way to murder. It makes no difference whether one destroys a soul already born or interferes with its coming to birth.

It is a human being and one who is to be a man, for the whole fruit is already present in the seed”.[10] A similar point is made by Minucius Felix (A.D. 170-215) in The Octavius 30.2. The ethos of Christianity from the age of the Apostles recognized the immorality of taking unborn human life.

As Christianity emerged from persecution, conciliar canons appeared against abortion, affirming the status of the fetus as a person. The first important local conciliar canon dates from A.D. 314, where Canon 21 of Ancyra lessens the penance for abortion to ten years (noting that the rule had been excommunication for life). In A.D. 315 the Council of Neocaesarea in Canon 6, speaking to the baptism of pregnant women, recognizes the child in the womb as a separate person. “As concerning a woman who is gravid, we decree that she ought to be illuminated whenever she so wishes. For in this case there is no intercommunion of the woman with the child, owing to the fact that every person possesses a will of his own which is shown in connection with his confession of faith.”[11] The second part of the canon appreciates the child in the womb as a person who requires his own baptism. The baptism of the woman does not effect the baptism of the child. The child must be separately admitted to the Church and immersed, which can only be possible after birth.

As Christianity emerged from persecution, conciliar canons appeared against abortion, affirming the status of the fetus as a person. The first important local conciliar canon dates from A.D. 314, where Canon 21 of Ancyra lessens the penance for abortion to ten years (noting that the rule had been excommunication for life). In A.D. 315 the Council of Neocaesarea in Canon 6, speaking to the baptism of pregnant women, recognizes the child in the womb as a separate person. “As concerning a woman who is gravid, we decree that she ought to be illuminated whenever she so wishes. For in this case there is no intercommunion of the woman with the child, owing to the fact that every person possesses a will of his own which is shown in connection with his confession of faith.”[11] The second part of the canon appreciates the child in the womb as a person who requires his own baptism. The baptism of the woman does not effect the baptism of the child. The child must be separately admitted to the Church and immersed, which can only be possible after birth.

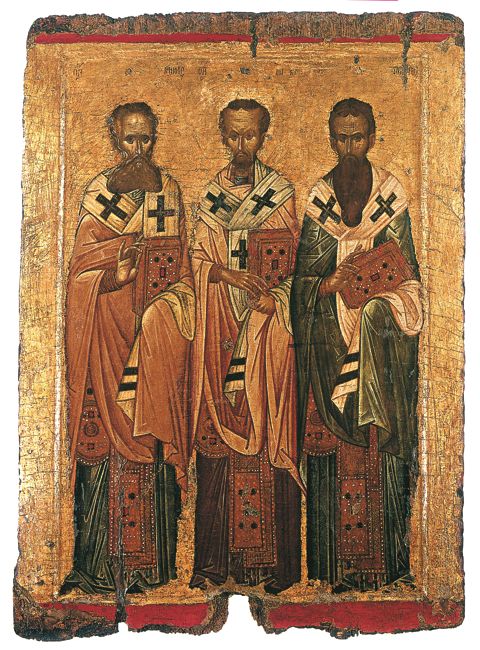

The canonical condemnation of abortion is repeated throughout the first two-thirds of the first millennium, solidly presenting the Tradition’s exceptionless condemnation of abortion. For example, St. Basil the Great in his second canon forbids abortion, as does St. John the Faster, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, in his Canon 21. Significantly, abortion is condemned by Canon 91 of the Quinisext Council, which articulates the canons for two ecumenical councils. This consistent position of Orthodox Christianity is taken without ever raising the question as to when the fetus is ensouled, much less drawing a distinction between early and late abortions. This is the case, even though it was well known that the Septuagint version of Exodus made a distinction between a formed and an unformed fetus, between an early and a late miscarriage due to a third party’s mischief.

The matter of the Septuagint deserves special attention, given its peculiar influence in second-millennium Western Christian circles. The passage reads, “And if two men strive and smite a woman with child, and her child be born imperfectly formed, he shall be forced to pay a penalty: as the woman’s husband may lay upon him, he shall pay with a valuation. But if it be perfectly formed, he shall give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe” (Ex 21:22-23).[12] The text currently accepted by Jews reads, “When men fight, and one of them pushes a pregnant woman and a miscarriage results, but no other damage ensues, the one responsible shall be fined according as the woman’s husband may exact from him, the payment to be based on reckoning. But if other damage ensues, the penalty shall be life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.”[13] Verse 22 of the current Hebrew text makes no distinction between unformed and formed fetuses, while verse 23 focuses only on injuries to adults harmed in a struggle.

The matter of the Septuagint deserves special attention, given its peculiar influence in second-millennium Western Christian circles. The passage reads, “And if two men strive and smite a woman with child, and her child be born imperfectly formed, he shall be forced to pay a penalty: as the woman’s husband may lay upon him, he shall pay with a valuation. But if it be perfectly formed, he shall give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe” (Ex 21:22-23).[12] The text currently accepted by Jews reads, “When men fight, and one of them pushes a pregnant woman and a miscarriage results, but no other damage ensues, the one responsible shall be fined according as the woman’s husband may exact from him, the payment to be based on reckoning. But if other damage ensues, the penalty shall be life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.”[13] Verse 22 of the current Hebrew text makes no distinction between unformed and formed fetuses, while verse 23 focuses only on injuries to adults harmed in a struggle.

Two points must be noted. First, the text does not address the issue of abortion, but instead concerns an instance of involuntary homicide. Second, the Septuagint version is not more permissive, but in fact more exacting in its punishment for involuntary homicide than the contemporary Hebrew version. The Septuagint version can thus be understood as an intermediate step between the more lax approach allowed by Moses and the more exacting and full understanding realized in Christianity. As Christ reminds us with respect to the case of divorce (“Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard” [Matt 19:8]), the Mosaic law took into account hardness of heart and, in some areas at least, required less of Jews than is required of Christians.

What is important for Christians is that a distinction between formed and unformed fetuses, ensouled and unensouled fetuses, is explicitly rejected as of no theological significance for Orthodox Christians. St. Basil the Great speaks clearly against accepting such a distinction with regard to the morality of abortion in his letter to Amphilochius (Letter 188). “She who has deliberately destroyed a fetus has to pay the penalty of murder. And there is no exact inquiry among us as to whether the fetus was formed or unformed.”[14] This position of St. Basil the Great must be set against two very important issues, the first moral, and the second scriptural. The moral issue involves the requirement that Christians not shed innocent human blood, a requirement reflecting a fundamental biblical prohibition (Gen 9:6) that is independent of any issue of ensoulment and expressed in Christianity’s exceptionless condemnation of abortion since Apostolic times. The second issue is Scriptural and is twofold. First, as already noted, the Septuagint version of Exodus does not minimize but renders more severe the juridical punishment required by Exodus for the involuntary homicide described. Second, what was required of the Jews under the 613 requirements of the Mosaic law in general, and with respect to abortion in particular, cannot without further careful examination be used to determine what is required of Christians. The Talmud, for example, recognizes that the law with regard to abortion is stricter for ben Noah (Gentiles) than for Jews (Sanhedrin 57b), so that according to at least some Orthodox Jewish scholars, while abortion would be permitted in many circumstances for Jews, it would not be permissible for ben Noah (Gentiles). Abortion for a Gentile involves violating one of the seven prohibitions of the Noachite Covenant and would be a capital crime.[15]

What is important for Christians is that a distinction between formed and unformed fetuses, ensouled and unensouled fetuses, is explicitly rejected as of no theological significance for Orthodox Christians. St. Basil the Great speaks clearly against accepting such a distinction with regard to the morality of abortion in his letter to Amphilochius (Letter 188). “She who has deliberately destroyed a fetus has to pay the penalty of murder. And there is no exact inquiry among us as to whether the fetus was formed or unformed.”[14] This position of St. Basil the Great must be set against two very important issues, the first moral, and the second scriptural. The moral issue involves the requirement that Christians not shed innocent human blood, a requirement reflecting a fundamental biblical prohibition (Gen 9:6) that is independent of any issue of ensoulment and expressed in Christianity’s exceptionless condemnation of abortion since Apostolic times. The second issue is Scriptural and is twofold. First, as already noted, the Septuagint version of Exodus does not minimize but renders more severe the juridical punishment required by Exodus for the involuntary homicide described. Second, what was required of the Jews under the 613 requirements of the Mosaic law in general, and with respect to abortion in particular, cannot without further careful examination be used to determine what is required of Christians. The Talmud, for example, recognizes that the law with regard to abortion is stricter for ben Noah (Gentiles) than for Jews (Sanhedrin 57b), so that according to at least some Orthodox Jewish scholars, while abortion would be permitted in many circumstances for Jews, it would not be permissible for ben Noah (Gentiles). Abortion for a Gentile involves violating one of the seven prohibitions of the Noachite Covenant and would be a capital crime.[15]

In short, these Orthodox Jewish authorities agree with St. Basil the Great: one may not argue, as the Roman Catholic church of the Middle Ages did,[16] from what was required under Mosaic law with regard to involuntary homicide to what is required from Christians with regard to abortion. Orthodox Christianity, unlike the West, acknowledges that the Mosaic law cannot directly be used as a guide for a proper understanding of the morality of abortion. St. Basil the Great’s position and the canons of the Church were affirmed by St. Photios the Great (810-895) in Syntagma Canonum and Nomocanon (as revised at the behest of Emperor Constantine VI), walling Orthodox Christianity off from the various novelties with regard to abortion that emerged in the Latin church beginning in the 12th century.[17]

In short, these Orthodox Jewish authorities agree with St. Basil the Great: one may not argue, as the Roman Catholic church of the Middle Ages did,[16] from what was required under Mosaic law with regard to involuntary homicide to what is required from Christians with regard to abortion. Orthodox Christianity, unlike the West, acknowledges that the Mosaic law cannot directly be used as a guide for a proper understanding of the morality of abortion. St. Basil the Great’s position and the canons of the Church were affirmed by St. Photios the Great (810-895) in Syntagma Canonum and Nomocanon (as revised at the behest of Emperor Constantine VI), walling Orthodox Christianity off from the various novelties with regard to abortion that emerged in the Latin church beginning in the 12th century.[17]

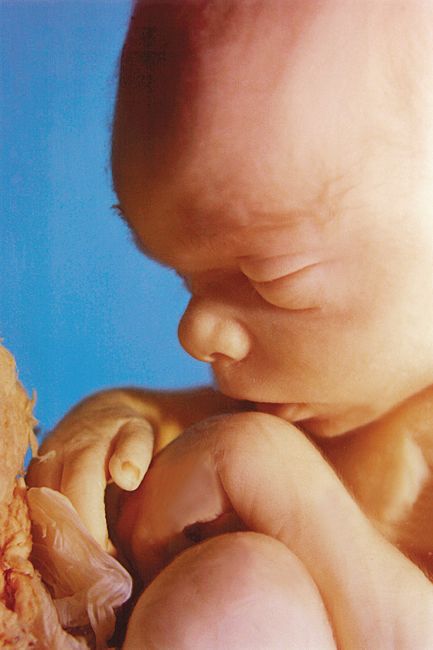

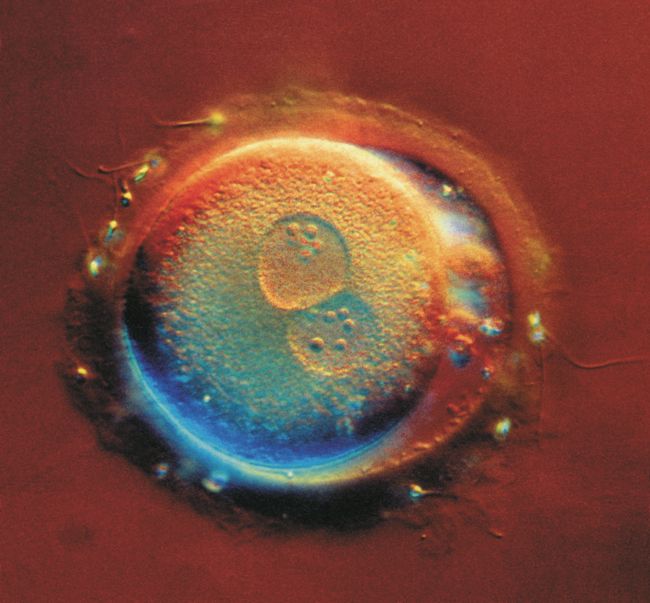

IV. Placing the Biological Facts in a Rightly-Ordered Theological Perspective

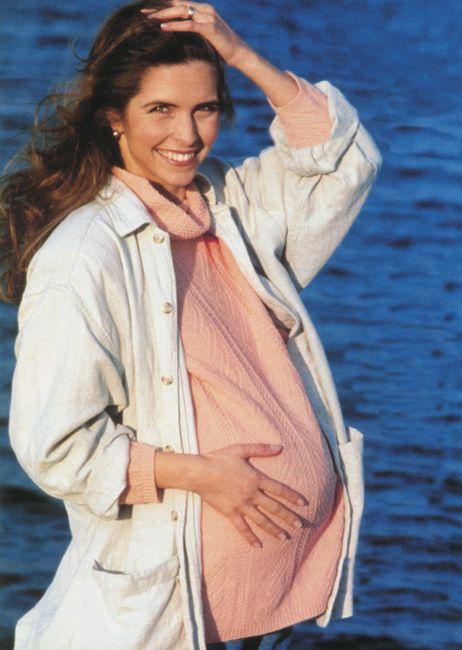

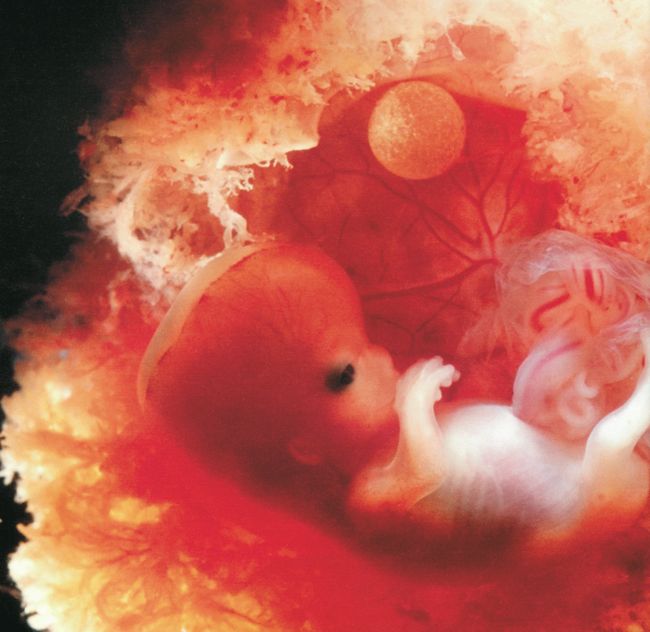

One only sees that which one knows how to look for. If one does not know that germs exist, one does not know to look for them, much less how to see them. So, too, if one has closed one’s heart to God, one fails to see Him, as well as how to come to Him. The consequences of worshipping wrongly include, as St. Paul emphasizes in Rom 1:23-28, perversion of one’s passions and a distortion of one’s conscience. If one embraces the secular culture, one does not rightly perceive what is at  stake in sexuality, reproduction, and abortion. If one rightly orients oneself to God, one easily recognizes the cardinal biological and moral significance of the zygote, the new human life that is formed with the fusion of human sperm and ovum. Though a possibility of twinning exists after this point both in nature and through illicit in vitro techniques, and even though there is a considerable spontaneous early embryo loss, one can with St. Basil recognize that any act to kill this new human life will have moral consequences equivalent to homicide, as Christians have clearly appreciated for two thousand years. Orthodox Christians can also speak against any action against the zygote, while not as in the West being confronted by a supposed dilemma between either not recognizing the embryo as a person, or recognizing an obligation to mount medical interventions to prevent early naturally occurring embryo loss. One will instead understand that there is no place for a moral distinction between a formed and unformed embryo. In addition, one will see the early life of a new child growing and waiting to be born. The capacities of modern medicine actually to show the living, growing child in the mother’s womb help dramatically to present the reality and life of the child who will soon be born.

stake in sexuality, reproduction, and abortion. If one rightly orients oneself to God, one easily recognizes the cardinal biological and moral significance of the zygote, the new human life that is formed with the fusion of human sperm and ovum. Though a possibility of twinning exists after this point both in nature and through illicit in vitro techniques, and even though there is a considerable spontaneous early embryo loss, one can with St. Basil recognize that any act to kill this new human life will have moral consequences equivalent to homicide, as Christians have clearly appreciated for two thousand years. Orthodox Christians can also speak against any action against the zygote, while not as in the West being confronted by a supposed dilemma between either not recognizing the embryo as a person, or recognizing an obligation to mount medical interventions to prevent early naturally occurring embryo loss. One will instead understand that there is no place for a moral distinction between a formed and unformed embryo. In addition, one will see the early life of a new child growing and waiting to be born. The capacities of modern medicine actually to show the living, growing child in the mother’s womb help dramatically to present the reality and life of the child who will soon be born.

Orthodox Christians live in an unbroken appreciation of how properly to regard human life from its conception, recognizing that any taking of that life is forbidden. They live in a vivid appreciation of why sexuality and reproduction must be placed within the life of a Christian family that seeks selflessly to procreate, and lovingly to raise children for the kingdom of heaven.

Orthodox Christians live in an unbroken appreciation of how properly to regard human life from its conception, recognizing that any taking of that life is forbidden. They live in a vivid appreciation of why sexuality and reproduction must be placed within the life of a Christian family that seeks selflessly to procreate, and lovingly to raise children for the kingdom of heaven.

Notes:

* Herman T. Engelhardt is professor, department of philosophy, Rice University, and professor emeritus, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

[1] One analysis of the global data indicates that somewhere between 36 and 53 million unborn children are killed by abortion every year. H. K. Henshaw, “Unintended Pregnancy in the United States,” Family Planning Perspectives 30 (1998), 24-29, 46. See, also, Wendy R. Ewart and Beverly Winikoff, “Toward Safe and Effective Medical Abortion,” Science 281 (July 24, 1998), 520-1.

[2] http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/policy/abortion/wrjp333pd2.html, updated March 23, 2004.

[3] http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/policy/abortion/ab-greece.html (updated March 23, 2004).

[4] Pace Plato’s Euthyphro, it is not simply that God approves of the good, right, and holy because they are good, right, and holy, nor is it simply the case that that which is good, right, and holy is such because God approves of it. Rather, it is the case that created being, including goodness, rightness, and a creature’s turning to the holy, can only be understood in relation to God, Who is Uncreated Being.

[5] Protagoras rejected the existence of the Divine and proclaimed that “Man is the measure of all things, of things that are that they are, and of things that are not that they are not.” Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers IX.51, trans. R. D. Hicks (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), vol. 2, pp. 463, 465. See, also, Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism I.216, trans. R. G. Bury (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), vol. 1, p. 131. Once the focus changes from God to human person, human dignity is no longer bestowed by God, but realized by humans in their free choice and their equal dignity.

[6] Infanticide was widely accepted in pagan Graeco-Roman culture. See, for example, Plato, Republic v.459ff, as well as Cicero’s remarks regarding Table IV of the Roman law of the Twelve Tables. “Destruction of deformed infants: Cicero: Quickly killed, as the Twelve Tables ordain that a dreadfully deformed child shall be killed.” E.H. Warmington (ed. and trans.), Remains of Old Latin, vol. 3, The Twelve Tables (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), p. 441. In practice, infanticide came to be widely used to dispose of an inconvenient offspring. The contemporary Princeton University philosopher and moral theorist Peter Singer recognizes and celebrates that contemporary culture is becoming like antique pagan culture in losing the ability to discern the evil in killing either a fetus or a human infant. As Singer argues, killing a fetus or a human infant should be considered morally on a par with killing a non-human animal of a similar level of psychological development. See, for example, Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: Avon Books, 1990), pp. 81-82, 240. Here, Peter Singer has an important insight into secular morality that accepts abortion as a means for terminating pregnancies. Severed from Christian moral insights, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, for this culture to justify any clear moral lines between killing a fetus and killing a young infant, between feticide and infanticide. It is for this reason that the pagan world accepted infanticide as easily as it accepted abortion. As Singer puts it, “Killing unwanted infants or allowing them to die has been a normal practice in most societies throughout human history and prehistory. We find it, for example, in ancient Greece…. The wide support for medical infanticide suggests that, instead of tying to find places to draw lines, we should accept that the development of the human being, from embryo to fetus, from fetus to newborn infant, and from newborn infant to older child, is a continuous process that does not offer us neat lines of demarcation between stages.” Singer, Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of our Traditional Ethics (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1994), pp. 129, 130.

[7] This term (pharmuakeusis) may identify the practice of sorcery or perhaps even the production of love potions against which St. Basil speaks in his canon 8.

[8] The Didache II.2, trans. Kirsopp Lake (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), vol. 1, pp. 311, 313.

[9] “Epistle of Barnabas,” in Apostolic Fathers, trans. Kirsopp Lake (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Pres, 1965), XIX 4-5, vol. 1, p. 403.

[10] Tertullian, “Apology” 9.8, in Apologetical Works, trans. Rudolph Arbesmann, Sr. Emily Joseph Daly, Edwin A. Quain (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1950), pp. 31-32.

[11] “The Fifteen Cannons of the Regional Council Held in Neocaesarea,” in The Rudder of the Orthodox Catholic Church, eds. Sts. Nicodemus and Agapius (New York: Luna Printing, 1983), p. 511.

[12] The Septuagint with Apocrypha, trans. Lancelot C.L. Brenton (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997), p. 98.

[13] Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (eds.), The Jewish Study Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 154.

[14] Saint Basil, Letters, trans. Sr. Agnes Clare Way (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1955), vol. 2, p. 12.

[15] Baruch A. Brody, “The Use of Halakhic Material in Discussions of Medical Ethics,” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 8 (1983), 317-328.

[16] Corpus Juris Canonici Emendatum et Notis Illustratum cum Glossae: decretalium d. Gregorii Papae Noni Compilatio (Rome, 1585), Glossa ordinaria at bk. 5, title 12, chap. 20, p. 1713. Between 1234 and 1869, save from 1588-1591, the Roman church did not consider early abortion murder.

[17] Thomas Aquinas, influenced by Aristotelian biology and philosophy (see, for example, Aristotle, De Generatione Animalium, 2.3.736a-b and Historia Animalium, 7.3.583b), failed to appreciate the evil of early abortion, leading him and his successors to draw a distinction between human biological and human personal life, from which they falsely derived both moral and canonical significance (in not appreciating early abortion as equivalent to homicide). See Thomas Aquinas, Aristoteles Stagiritae: Politicorum seu de Rebus Civilibus, Book VII, Lectio XII, in Opera Omnia (Paris: Vives, 1875), vol. 26, p. 484. See, also, Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I, Q 118, art. 2, reply to objection 2.