The Elder Joseph the Hesychast (+1959) Strugles, Experiences, Teachings (12)

19 Οκτωβρίου 2009

10. From St Basil to Little St Anna

‘The solitaries lead a blessed life, for divine love gives them wings.’

Once someone’s heart is struck by the darts of this love, then nothing, no pretext or reason, can bind him or hold him captive. ‘Let’s go, Arsenios, let’s go! We have lost too much of our freedom from care and our stillness. Let’s go somewhere else to carry on our struggle, where we are not known, so that people can’t easily find us and deprive us of what we then lose, and they can’t even see!’

From information from older fathers of St Anna, they found out about some caves over by Little St Anna. These were below the hermitage of the ever-memorable Father Savas, the spiritual father, towards the sea; some Russian monks had lived there at one time, and two small cisterns were still preserved. When they had investigated the place and found that it really was a suitable and quiet place, isolated and hidden from the mass of people, they took up their poor clothes and a few books and settled themselves there. That was winter time, January 1938.

The beginning was really very hard and cheerless, because everything was in short supply, even the bare essentials. But the great trial for the Elder had to do with the Liturgy, because he could no longer walk at all, particularly on an uneven road. His many labours, bitter struggles, extended fasts and all the other manifestations of his zeal for the struggle, in which he had no intention of letting up at all, had enfeebled and subdued his body so that he could only just force himself to move about to look after himself. Father Arsenios bore the brunt of the work and fortunately he was by nature strong and resilient, and they prepared a place for themselves there in whatever makeshift fashion they could.

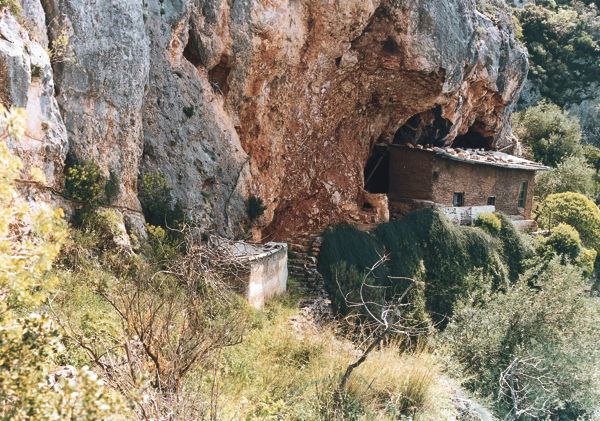

First they built the enclosure with a small gate and began once more to follow their rule, according to which they worked and received visits for half the day, and after midday they kept stillness and closed the entrance gate. Then they built a makeshift little chapel in a cave, dedicated to St John the Baptist, where they could have a Liturgy once or twice a week. They cleaned out and repaired the two cisterns and put the pipes into the rocks to collect water. Then they built a larger hut with wood and branches and clay, and divided it into three cells. They built out as far as the topography permitted, so that the inner part towards the cave could serve as a small storeroom.

I am describing here the physical state and quality of the place where they were living, and perhaps some may think I am making too much of it. Be that as it may, I have to say something about this now that I have touched on the subject. Besides, I think that the surroundings in which a person lives can give an indication of his character, in some aspects at least, because his movements and choice of a place to live, like his behaviour, correspond to his disposition and purpose. Of course, the primary reason for this austerity was the Elder’s divine zeal for asceticism. But there was also a secondary reason, which dictated their cramped conditions and restricted space, and that was the unsuitability of the terrain. There is a sheer drop in that place. From the top of a high and sheer rock down to the sea, there is no wider place where one could settle oneself or create even the indispensible basics. The frequent rockfalls necessitated sheltering under the caves or wherever there was a protected spot. In the three cells into which their hut was divided lived the Elder and Father Arsenios, and in the third the priest when he came for the Liturgy. These cells were very small, so that someone with very modest requirements could only just be accommodated. The dimensions were 1.8 by 1.5 metres, and instead of a door there was a window.

The riches of poverty which filled the inner man with experience of God restricted to a minimum their various needs. The mind which swims in the calm of freedom from care avoids as far as possible the care of too many things and materials. This is why we found virtually nothing when we went to stay with them in the summer of 1947.

Love for a quiet life free from care, and the fruits of the Spirit that are engendered by this, have often lured our Fathers to forget the law of mutual support and love at certain times so as not to be deprived of the turning towards God that they yearn for, alone before Him alone. This language is known only to people who have personal and practical experience, and who understand those who are full of zeal for this life of struggle.

This was the reason why the Elders replied in the negative when I asked them to let me stay with them and become a monk with them. ‘The space doesn’t allow it, my boy, and our regime has no room for others here’, was the reply. I did not lose heart and repeated my request more imploringly, until I extracted the promise that they would pray, and do as God enlightened them to. When on the next day, after an agonising wait, I heard the Elder’s consent to accepting me, it opened up a new page in my life. Only from then on I had no doubts or misgivings, but with all the fullness of assurance and faith I had found what I longed for and planned for, which had also been my dream from afar. The conclusion I had come to, from what I had read of the counsels of the Fathers and from the oral advice given by Elders at our first monastery, was that progress in spiritual life and salvation is absolutely dependent on the spiritual guidance of an experienced Elder. I do not know whether this conclusion of mine was overstated, but anyway this conviction had taken hold of me to such an extent that it was wholly impossible to replace it with any other theory or with a second-rate monastic life. This is why I say that a new page in my life had opened up.

Labours, deprivations, austere surroundings, the thoroughly makeshift lodgings – because there was no permanent cell for me at least twice a week – the unfamiliarity of having to carry loads, which was the rule there, the inadequacy of my clothing – because I had no winter clothes with me – generally everything that went to make up the regime there and all the living conditions were very harsh and cheerless. But all this did not cause me any doubt but only joy, combined with a secret fear that something on my part might make the Elders decide not to let me stay on.

We would work up to midday on whatever needed to be done. Then we stopped and did Vespers with the prayer rope, alone, or a little reading. Then we came together for lunch, or rather dinner. Then we received a blessing from the Elder and go to our cells and sleep. After our rest, we would prepare anything that might be needed for the next day, and then each go to his own cell for prayer and vigil until midnight. If there was to be a Liturgy, it would take place then, after midnight, and if not there was spiritual study. We youngsters were allowed to visit the Elder at this time, to tell him our thoughts and hear his advice.

The Elder was profound, thoughful and experienced. He had no need to ask in order to analyse problems and respond: I was at a loss how he knew in such detail what I had within me, when I would have had difficulty describing it myself! When I went there, right from the first day he explained to me in detail the meaning of the spiritual life. In particular he attempted to explain to us about Grace, how this is the chief element that should concern us because without it man can achieve nothing. Gradually I grasped the meaning of his words, helped by my earlier studies and advice, but in practical terms I was ignorant of both the manner and form of the operation of grace.

I was living with them permanently by the time the Elder left the cell where he had been staying and went about 200 metres further away to another cell that I had prepared for him, and lived there on his own. After our vigil up to midnight we would go to the Elder, because he never received people earlier. One afternoon after our meal, as I made a prostration to him in order to go to my cell as usual, he clasped my hand and said to me, smiling, ‘Tonight I’m going to send you a parcel, and you must take care not to lose it.’ I did not understand what he meant and did not think about it at all, and I went off. After our rest, as always, we began our vigil and I prepared to begin my prayer as he had shown me, keeping hold of my intellect as best I could, and I forgot all about the parcel.

I do not remember how I started off, but I know very well that I had just begun and had not pronounced the name of our Christ many times before my heart was filled with love for God. Suddenly it increased so much that I was no longer praying, but wondering in amazement at this outpouring of love. I wanted to embrace and kiss all people and the whole of creation and at the same time I was so humble in my thoughts that I felt I was the lowest of all creatures. But the fullness and the flame of love was for our Christ, whom I experienced as present, although I could not see Him to fall at His spotless feet and ask Him how He could set hearts on fire like this and remain hidden and unknown. Then I had a subtle assurance that this was the Grace of the Holy Spirit and this was the Kingdom of Heaven, which our Lord says is within us (Lk 17:21), and I said, ‘Let me stay like this, my Lord, and I won’t need anything else.’ This went on for quite a time, and gradually I came back again to my former state and waited in an agony of impatience for the time to come when I could go to the Elder and ask him what this was all about and how it had happened.

It was about the twentieth of August and the moon was very bright, when I ran down and found him outside his cell, walking in his little courtyard. As soon as he saw me he began to smile, and before I could make a prostration he said, ‘You see how sweet our Christ is? Do you understand in practice what it is that you keep asking me about? Now exert yourself forcibly to make this grace your possession, and don’t let negligence steal it away from you.’ At once I fell at his feet and said with tears, ‘I’ve seen it, Elder; unworthy as I am of all creation, I have seen the grace and love of our Christ, and now I understand the boldness of the Fathers and the power of prayers.’ When I told him exactly what had happened and asked for details about how this had come about, he refused, out of humility, to tell me; so he said, ‘God had compassion and mercy upon you, showing you His grace by anticipation, so that you won’t doubt the counsels of the Fathers and lose heart.’ I then understood the meaning of the common custom of asking other people to pray for us, with full faith and trust: ‘Pray for me, Father. Say a prayer for me, Father. Remember me in your prayers, Father.’

There are many ways, of course, in which we Christians seek the assistance of the righteous in our needs, and each receives a response accordingly. But for a spiritual man to understand the need of a soul whose state he clearly discerns, and to instruct someone, ‘Go and mind that you receive what I’m going to send you – what you need’, and to know what he is sending and whether it has been received – all this exceeds the bounds of the natural and belongs to those who have gone ‘beyond nature’.

This was not the first time that we had seen consolation from the Elder’s prayers; and don’t tell me that it is natural for disciples to feel the blessing of their Elder. There is also that, of course, and blessed are they who have faith in their spiritual Fathers, because they are truly protected by their prayers. But in our case something else was happening, something higher and more significant. It is one thing for the disciple, in his faith and piety, to draw secretly on the help of grace on elementary points and situations, so that he is saved from dangers and difficulties, receives answers in various quandaries and in general enjoys an unseen blessing which guards him in everything. This is enjoyed by anyone who is under obedience even in a rudimentary way, and even without the knowledge of his elder, who is truly amazed at God’s blessing when his disciple tells him about it. But it is another matter for the Elder himself, as one having authority, to send grace and blessing to his disciple or wherever else, in the degree he wants and whenever he wants, with his own certain knowledge and on his own initiative. This is characteristic only of truly spiritual people, those who, in St Paul’s words, ‘judge all things, but are themselves to be judged by no one’ (1 Cor. 2:15). ‘The Spirit’, our Lord tells us, ‘blows where It wills, but no one knows whence It comes or whither It goes’ (Jn 3:8). So also are those who have the spirit and mind of Christ (cf. 1 Cor. 2:16).

This was not the first time the Elder had given us relief and assurance. As many will remember, the post-war situation was not normal; and for monks of the dependencies , like us, there were difficulties in getting the necessities of life. The handicrafts that we usually did were not in demand, and money did not circulate freely either. So it was only by hiring ourselves out to work that we could make a living, moving from place to place. We picked olives at the monasteries on a percentage basis, or hazelnuts, or we would go to pick grapes or work in gardens or do other jobs of that sort, until stability returned and we could take up our handiwork again. During this time when we were doing outside jobs I would go with other brothers, disciples of other Elders, from the wilderness where we lived to the various monasteries where we could find work; sometimes it was a long time before we returned to our huts, and so we were far from our Elder. For me this was rather difficult, because I had only just met the Elder and had not yet had the training to give me a really firm foundation, nor was I properly used to the Athonite spirit, and I found this very tiring. Whenever it happened that I got very tired, so that my patience gave out or some problem I had came to a head, then a letter would come for me from the Elder on the regular line between Scete and Daphne. There I would find written down the state I was in, and the reason for whatever was preoccupying me and where it came from. And the strange thing was that even before I opened it, a change would take place within me; all sadness vanished and I was filled with spiritual joy, and I was no longer concerned about any of the things that had been choking me with worry a short while before! At other times this happened even without a letter, just with the awareness of the Elder’s presence in a supranatural manner and I always understood this, when it approached me in a manner that left no room for doubt.

To be continued…