Byzantines beat the Vikings to America by 500 YEARS!

11 Ιουλίου 2009

"Main Altar" with Greek Doric style plinth. To the left is fish-shaped cupule (holes) pattern. Both hold candles for ceremonies. Photos courtesy of the author

Connecticut’s 5th Century Church

by John Gallager

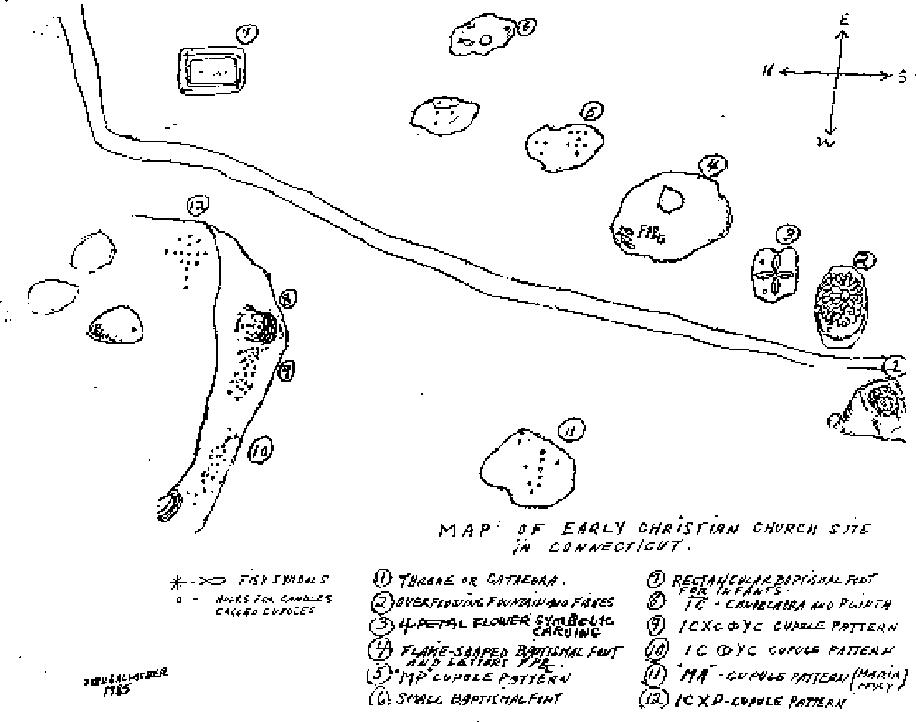

In the stillness of Cockaponset State Forest, southern Connecticut, near the town of Guilford, masterfully carved from solid rock, stands North America’s oldest Christian church. Recent epigraphic evidence found here suggests that it is 1500 years old, and linked to a voyage of Christian Byzantine monks who fled from North Africa during the 5th Century, in the wake of the Vandal invasions. Greek and North African inscriptions, Greek cupule patterns in the form of Chrismons (monograms of Christ), baptismal fonts, a cathedra or throne, candelabras and an altar have been found at the site.

MORE…

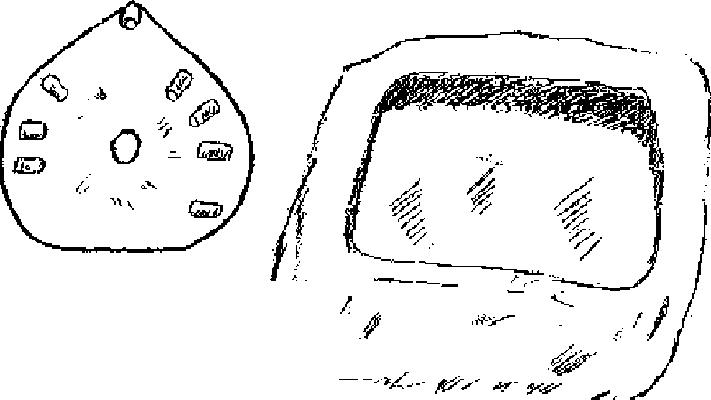

Flame-shaped Baptismal Font representing the Holy Spirit. Here the elderly were baptized by pouring water over their heads.

These items indicate that it was a place of worship, an Early Christian Church. The artifacts are illuminated by Libyan Arabic texts found at Figuig (Hadj-Mimoum), a remote oasis in eastern Morocco, in 1926. They tell of a voyage undertaken by North African Christian monks sailing “toward the set¬ting sun,” to “Asq-Shamal,” the “Northern Land,” suggestive of North America. A diffusionist scholar, Frederick J. Pohl, who studied the Figuig inscriptions during the 1960s, placed the monks arrival in North America at about 480 AD.

About 40 years ago, he was told of some strange carvings on stone in the Connecticut woods, and obtained the services of a local a physician as a guide to their location. As the author of several books describing Norse voyages to America, Pohl anticipated Viking origin for the Connecticut inscriptions. Seeing them in person, however, he knew at once that they were not 10th Century runic, but belonged to something entirely different and much older. Seeking clues from the immediate environment, he noticed a nearby cove suitable as a land-fall for ships was visible from the inscriptions.

When I first met an older Frederick Pohl at his home in Brooklyn, New York during 1976, he asked me to go to the site, look it over and see what I could make of it. For two and a half years thereafter, I regularly visited the site gathering information, taking photographs and making drawings, followed by long hours investigating source materials in public and university libraries. Together with Pohl, I sought out the opinions of other experts in pre-Columbian matters. Their insight combined with diligent, independent research to reveal the Guilford location as an Early Christian Church and Baptismal site of Byzantine Greek North African origin. Epigraphic evidence identified its construction or carving by Christian monks who voyaged to Connecticut from North Africa in the mid-5th Century.

To understand the origins and reasons behind this 1600 year-old undertaking, something about the history of the Early Christian Church during this period is needed. By 430 AD, more than 600 bishops operated across North Africa, mostly in Tunisia, where Christianity sank its roots in the Dark Continent at the ancient Phoenician port-city of Carthage. From the beginning, the new faith was a tale of violence and heresy. Under Emperors Decius (249 to 250), Valerian (257 to 259) and Diocletian (245 to 313), many Christians everywhere were arrested, tried and executed on charges of theological or political subver-sion, because they characterized the deities of all other faiths as “devils” and called for the downfall of the Roman state.

Meanwhile, fanatic followers of Manichaeism, Montanism, Pelagianism, and a dozen other, largely forgotten heresies fought bitterly between themselves

"Overflowing Fountain" sculpture containing fishes. The fishes are the newly bap¬tized Christians swimming in the waters of eternal life."

for control of Christianity. Among them was Arianism, after a late 4th Century Alexandrian priest who preached against the alleged divinity of Jesus. Arius claimed that the Christian Holy Trinity was a descending Triad with only the Father as the true God. Jesus was considered the Son of God, but only through by grace and adoption, and was neither co-equal nor co-eternal with the Father. Because they stressed the human nature of Christ, Arius and his followers were condemned as heretics by the Councils of Nicea in 325 AD and fifty-six years later in Constantinople.

Even so, Arianism spread to throughout the Germanic tribes of Northern Europe. Fleeing from other barbarians, the Vandals crossed into North Africa during early the 5th century, remaining there for over a century, until 534 AD. Saint Basil and Saint Augustine had introduced the cenobitic or “common life” form of monasticism into North Africa, the latter saint forming his rules for monks as early as 388 AD. Meanwhile, North Africa was ruled by six Vandal monarchs, three of whom (Geiseric, Huneric and Thrasamund) vigorously persecuted their fellow Christians in the Roman Catholic Church. Huneric sent many bishops in an attempt to purge monasticism from North Africa. Geiseric drove many monks from the deserts and mountains of eastern Libya in the latter part of the 5th Century. Only after Roman Emperor Justinian sent his General Belisarius to conquer the Vandal army in 534 AD were non-Arians able to safely return to North Africa.

Destruction wrought by the Vandals and the end of these “years of trouble” by the “trousered men”(Vandals) was vividly described in the Figuig inscriptions by a monk who returned to his homeland after the Vandals defeat. He also described the voyage of fellow ascetics to North America: “In the name of the hermitage of the fraternity now dispersed abroad, by oath sworn to Christ the Lord, the testimony of an eyewitness who has returned home by ship, that has put into the seaport, now in his homeland, a second time. Ended are the years of trouble by the trousered men.”

The author wrote of destruction by fire, looting, and the eventual escape of the monastic community “toward the setting sun,” to Asq-Shamal, or the Northern Land, in several ships. “Across the void of waves,” guided by a “cross-staff by which to sight positions of the sun and presumably the stars, and using calculations known only to their “helmsman,” they crossed the Mid-Atlantic Ocean. After months at sea, they made landfall in an unknown country, then “ventured into the wilderness.”

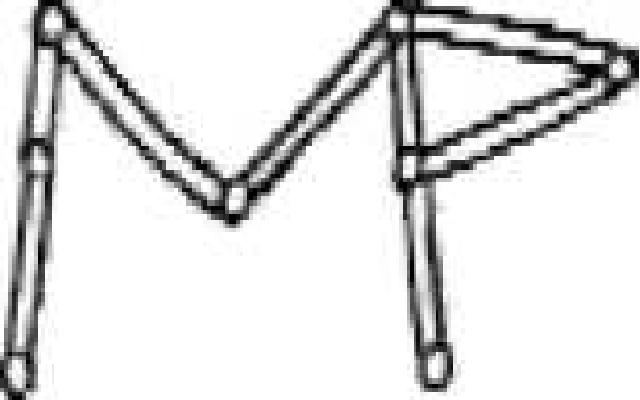

The inscription refers to a “North and West course from Morocco.” At the southern Connecticut site, 96 holes or cupules have been found. All are in the form of Chrismons or monograms of Christ and the Blessed Mother Mary. Some are also acrostics in the shape of a fish spelling out in abbreviated Greek letters a theological statement about Christ. An acrostic is a verse or arrangement of words in which certain letters in each line, such as the first or last, when taken in order, spell out a word or motto. The Guilford holes or cupules were used for candle-like objects known as tapers. The cupule pattern of holes drilled into the rock face of an apparent altar spells out the ancient Greek Christian ICX-COYC, an acrostic for Iesous Christos Theos Yios Soter, or “Jesus Christ Son of God Savior.”

Appropriately, it is in the shape of a fish, an early Christian symbol for “Jesus” and “baptism.” When Christianity was an underground movement in Rome, its followers recognized each other by each sketching one half of a fish, connecting the two sides together to form a Chi-Rho, the first two letters in Greek for Christ’s name (XP for XPIC-TOC, or “Christ”). The likeness of a candelabra has also been found at the Connecticut site, carved into the right side of the large rock outcrop referred to as the “altar.” It is adjacent to the fish cupule pattern.

The candelabra features 14 holes which were used to hold candles or tapers, with a seven-level plinth or base below. The 14 holes incised into the horizontal surface of the altar niche spell out the Greek letters IC with a ligature of Byzantine style above it. “Ligature” refers to a written character containing two or more united or combined letters, such as ae. IC are the first and last let¬ters of the Greek word IHCOC, Iesous, or “Jesus.” The Byzantine style ligature above these letters, also composed of holes, binds the two letters I and C together to form the name of “Jesus.” The plinth or base of the candelabra is Doric Greek in style.

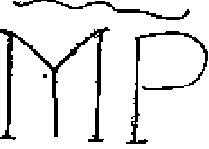

Also found at the site is another cupule pattern that spells out the Greek letters MP, the first and last letters of the Greek word Meter or “mother,” here referring to the “Blessed Mother Mary.” These two forms can be seen in the former Byzantine Cathedral of Sancta Sophia in Constantinople, now an mosque. They were uncovered by archaeologists presently engaged in their restoration. The modern name of

Left: Flame shaped baptismal font with holes for candles. Right: Rectangular Baptismal Font for Infants

Constantinople is Istanbul, now part of modern Turkey. Flanking the mosaic of the Blessed Mother Mary and the mosaic of Christ are the letters MP OY or Meter Theou, “Mother of God,” in Greek. On the mosaic of Christ are the Greek letters IC XC. In Byzantine Greek form with a ligature above it, the translation is Iesous Christos, or “Jesus Christ.” These examples date from the 9th Century, but the others can be seen in Rome’s 5th Century Santa Maria Maggiore, as well as from other churches of the period.

Found also at the Connecticut site are two extremely impressive baptismal fonts; one rectangular, the other in the shape of a flame, representing the Holy Spirit. The flame-shaped baptismal font is carved into a large rock outcrop which also contains the letters FPBC, probably an abbreviated form for the Latin words Fons Pro Baptisimus Catechumen, or “Font for the Baptism of Catechumens.”

Incised into the flame-shaped baptismal font are nine holes for candles. Eight holes, when containing lighted candles at Easter, could have represented the eighth day after the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, the beginning of the New Era, also signifying a second (spiritual) birth for baptized Christians. The flame shape represents the Holy Spirit received at Baptism. The ninth hole in the middle of the font stands for the Paschal candle, symbolic of Christ. Here the elderly were baptized by effusion, or the pouring of water over their heads.

The rectangular baptismal font a short distance away was used for the ablution of infants who were lowered into its waters by a priest while baptizing them in the name of the Holy Trinity. The three times they were lowered into the font represented the three days Jesus remained in the tomb before his resurrection; the rectangular baptismal font represented Christ’s tomb. A similar ceremony probably occurred at the nearby cove, where adults were baptized by being lowered into the waters three times, in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

A beautifully crafted symbolic carving representing overflowing water and fishes protruding from the waters lies nearby. It is symbolic of the newly baptized Christians (who were known as “little fishes”) emerging from the waters of eternal life after being baptized.

Another carving forms a rock seat or throne in which the bishop or abbot sat while conducting a “confirmation” cere¬mony, presiding over the newly baptized Christians and the Baptismal ceremony itself. Carved into one of the rocks is a four-petaled flower signifying the Christ and the newly baptized Christians.

Like Jesus, believed to have flowered from the stem of Jesse and David, the newly baptized Christians were intended to bloom and flower into holy Christianhood. Such imagery was suggested by an Old Testament passage announcing the arrival of Jesus from the house of Jesse and David: “He will flower from the rod (Nazareth) and the stem (house) of David and Jesse.”

Kensington Runestone is going to Sweden

The Runestone Museum of Alexandria, Minnesota is pleased to announce that the Kensington Runestone traveled to Stockholm, Sweden in fall to take part in an exhibit of Swedish Runestones. Invitation by directors of the Statens Historiska Museum in Stockholm, Sweden, was prompted by their review of extensive new research on the stone.

Richard Nielsen of Houston, Texas, Scott Wolter of Chanhassen, Minnesota, and Runestone Museum Executive Director, LuAnn Patton traveled with the Kensington artifact to present their findings at a conference organized by the Statens Historiska Museum on October 23rd. The focus of the Swedes’ research was on the geological aspects of the stone, as well as various aspects of the written language featured in the inscription.

It is truly gratifying to realize that the Kensington Runestone has at long last become a serious object of study by Scandinavian scholars after more than a century of official ridicule and indifference. Found in 1898 by Swedish immigrant farmer, Olof Ohman and his son, Edward, for years thereafter the runestone was at the center of an on-going controversy. A translation of its carved text reveals that Scandinavians arrived in Minnesota about seventy years before Columbus left Spain for the New World.

High-tech research over the past three years renewed interest in the question of its authenticity, however. Scholars, researchers, and professionals from all over the world travel to Minnesota’s Runestone Museum to learn first-hand about this intriguing artifact. The Kensington Runestone will remain in Sweden until January, 2004. Meanwhile, its exact replica remains on display in Alexandria museum.

An inscription, carved in two languages, has also been recovered from the site. A scholar requesting anonymity believes one is in Mic-Mac, an Indian tongue of Nova Scotia, while the other is Greek as was spoken in Cyrene, Libya. In his translated interpretation of the inscription, the Lord is the eternal father of his children, mankind; the Redeemer has ascended into Heaven, and sits at the right hand of the Father. A word appearing in the text, Chrismon, or ICYTH-XPICTOC (“Jesus, Son of God, the Messiah”) is an abbreviated form in accord with the Byzantine and North African Church of the Vandal period.

ARoman Catholic priest of New York City, Father John O’Connor, has identified the Guilford inscription as a paraphrase of the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Romans (Chapter 8, Verses 14-17 and also Verse 34). The writing style is 5th Century Greek, just when the Vandals invaded North Africa, where Lybian Cyrene was one of the oldest Christian bishoprics. Some 100 miles or more to the East, also in Libya, lay Adrimachidae from which some of the Christians who made the Connecticut carvings are believed to have originated, based on linguistic affinities between the Greek spoken there and that represented in the Guilford text.

Others who contributed to the inscription, as the Figuig Decipherment or inscription proves, were from Morocco. Since the Vandals’ powerful navy controlled the western Mediterranean, these and other early Christian groups from North Africa must have endured an arduous journey to the sea coast of Morocco, before attempting to cross the Mid-Atlantic Ocean. Inscriptions, acrostics and symbolic carvings found at the Connecticut site are evidence for the arrival of these Orthodox Christians from the persecution of Arian Vandals in Lybia. Ruins of the church they built confirm their landfall in America a thousand years before the official arrival of Christianity with Christopher Columbus in 1492. n

John Gallager is a historical detective. He has a B.A. in history from Fordham University, New York City, NY. He is the former epigrapher consultant for the American Institute of Archaeological Research in New Hampshire. He has written several articles on the early explorations into North America.

Source: Ancient American • Issue Number 54