The Early Centuries of the Greek Roman East (3)

30 Μαΐου 2009

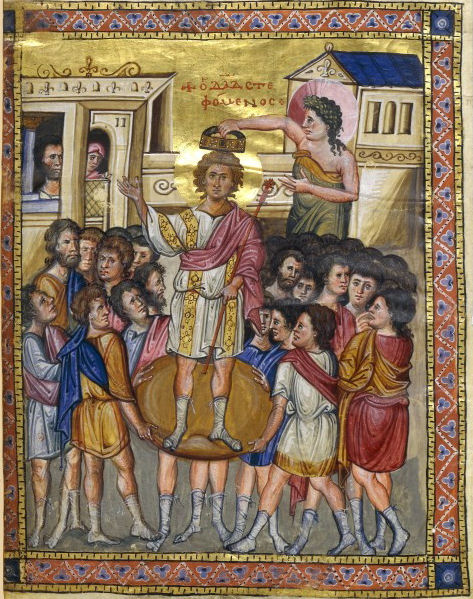

The coronation of David. Miniature from the byzantine Psalter of the National Library of Paris (early 10th century). Ο Δαβίδ στεφόμενος. Μικρογραφία από το βυζαντινό Ψαλτήρι της Εθνικής Βιβλιοθήκης των Παρισίων (αρχές 10ου αιώνος).

Literature and the Arts

Outside the Augustaeum, in Constantinople, one would notice a statue of Justinian wearing what was known at the time as the armour of Achilles. But the Emperor carried no weapon. Instead he held in his left hand the symbol of power of the Christian Roman Emperor, the globe, which signified his dominion over land and sea, and on the globe was a cross, the emblem of the source of his rule. Justinian as Achilles was a natural example of the fusion of classical culture with Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire. This fusion begun before Justinian’s time but was to continue to be one of the distinguishing marks of education and literature in the age of Justinian. Along with the legal and architectural splendours discussed above, the reign of Justinian also saw a flowering of literature such as the Greco-Roman world had not enjoyed for many years.

The earliest Christians avoided the worldly learning of the Greeks with their “philosophy and deceit”, and saw no way in which the blasphemous literature could be brought into any sort of relationship with Christian teaching. This reaction of many Christians, as late as the second century, could be summed up in Tertullian’s famous phrase, “what has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” In time, however, Christian thinkers began to realize that there was much to be carried over into Christian teaching from the Classical Greeks. Socrates and Plato, for example, often seemed to approximate Christian thought. Likewise many of the writings of Aristotle could be fit right into the teachings of the Church. MORE… Indeed after the adoption of Christianity people such as St. Basil and the other fathers of the Church, all trained in Greek literature, were able to show that Pagan literature contained a wealth of teaching that was in accord with the philosophies, dogmas and symbolism’s of Christianity. It is true that such literary themes as the loves of the Olympians, and the witty humor of Aristophanes, represented views of life that Christianity came to replace. However, the fathers of the Christian Church and other later thinkers had the insight to perceive that it was possible to make some basic distinctions, and separate those elements from classical literature that were not in accord with Christianity, keeping all the rest. The writings of the Fathers of the Church, and many others after them show an established conviction which was vital for the future of the Byzantine civilization, and indeed, all Christian cultures. This conviction brought about the establishment of a “new” Christian culture, one utilizing all the best writings of the classical Greek thought and fusing it into the writings and teachings of the Orthodox Church. The process of such a fusion took centuries, and its final step was not to be completed till the age of Justinian.

Even after Christianity had grown to the point where numbers of prominent people were Christians, public life was still in the hands of people who had a classical education By this time the educational system had come to be viewed as the embodiment of the ancient heritage, political and philosophical as well as literary. In the Greek East, even under Roman subjugation, Greek literature kept alive for centuries the tradition of the political, philosophical and artistic achievements of the classical Hellenic world. For a Greek Christian to give up all the classical teachings simply because parts of them were indelicate would have meant loosing a great deal. It would have meant, had he chose to accept only the teachings of the early Christians, that he would be cut off from a major part of his cultural heritage. Most people were not prepared for this.

It was into a world founded on this ideology that Justinian came. Indeed, Justinian immediately recognized the meaning of the classical spirit and set himself to absorb it and be absorbed by it. The Greek language itself also fascinated him and he took great pleasure in composing state papers in it, although he had a skilled secretariat for this purpose. A humorous anecdote in this vein comes to us in Procopius’s “secret history”, where he tells us rather wickedly that the Emperor took great pleasure in performing public readings of his works, in spite of his provincial accent, which he never lost when speaking Greek (of course, who was to tell the Emperor that his accent was provincial?)

Justinian decided to put an end to the idea of Paganism as heresy. He saw, however, that there was a major problem in the manner in which Pagan writing was being taught in the schools and universities. In particular, it was being taught in two different ways.

In the schools of Constantinople, Gaza and Alexandria, the classics were being taught by teachers who were themselves Christians. Procopius was typical of such Christian teachers steeped in the classics.He and his pupils and colleagues composed great ecclesiastical works based on the classical style. The theaters of Gaza were often filled with Christian professors who would give public exhibitions in which they declaimed before enthusiastic audiences their rhetorical compositions. Another such teacher, alive in Justinian’s day, was John Philoponus. His works included both theological treatises and polemics, as well as commentaries on Aristotle. One center of learning that even until Justinian’s time had never associated itself with Christianity was Athens. There the professors were still Pagan and were teaching the classics from entirely the Pagan point of view. This was found unacceptable. Not the fact that they were teaching classical works, but that they were themselves not Christians. Justinian gave them the opportunity to become Christian but they refused. As a result Justinian closed down their schools in 529, his second year as emperor. Of course, one could still continue to study the classics at Alexandria, Gaza, or Constantinople, where the teachers were Christians. Most of the Athenian professors went as refugees to the court of the King of Persia. However in time they found conditions there even worst and they petitioned to be allowed to return home. For better or for worst, this action of Justinian’s was to be symbolic of what the “new” Christian education and literature, based on the classics, was to be like henceforth.

The favorable atmosphere of the capital city, Constantinople, produced a number of distinguished literary figures in Justinian’s time. Many of their works were largely influenced by the teachings of Aristotle, Plato and other ancient Greek philosophers and play writers, whom they had all studied. Indeed men in public life were frequently scholars and poets. The work entitled “The Greek Anthology”, for instance, preserves selected specimens of the verses of nine such poets. Included in this list is John the Lydian, who wrote some autobiographical passages about the scholarly side of the government, and also a history of the Persian war. As already mentioned, Procopius the historian, and Paul the Silentiary were also in this list of distinguished scholars at the time of Justinian.

Procopius studied at Gaza, then a university town, and learned to mimic the style of the great Greek historians such as Herodotus, and Thucydides. In 527 he went to Constantinople where he was to assume new heights as the leading historian of the day, as well as a legal advisor to Belissarius, the most brilliant of Justinian’s generals. As we saw above he also wrote a panegyric in which Justinian’s vast construction program was described with the resources of literary art. After Procopius’s death another of his works, “The secret History” was published, in which he libelled the Emperor Justinian who, he believed, had failed to do justice to his hero Belissarius.

While Procopius went back to the classic Greek historians, Paul went back to Homer. He wrote a famous description of St. Sophia in 887 hexameters, about the length of one of the longer books of Homer. Homer became the vehicle for the praise of the noblest church in the empire. Like Procopius’s earlier work Paul’s monograph on Agia Sophia reflects a real Christian feeling via the subtlety and similies of the Homeric style. It was not only for his praise of Agia Sophia that Paul is known for, however. In his day and later Paul was one of the most appreciated writers of occasional verses in the Classical style. The seventy eight of his epigrams which are preserved in “The Greek Anthology” show that he was an accomplished practitioner of the classical style and, with an intimate knowledge of classical literature and a delicate feeling for language and meter.

In the age of Justinian, Greek classical literature was a part of the ancient heritage, and Christianity, as a custodian of this heritage, was well able to absorb the classical literary tradition so long as it was understood that the tradition now played a vital role as an element in the new and larger Christian way of life that Hellenism and the entire Eastern Roman Empire had gradually evolved into. Justinian knew that true patriotism and national pride would come from the teaching of the record of achievements of ancient Greece. Indeed, the Greek-speaking citizens of the empire were very conscious of their decent from the Greeks of ancient times who had produced the likes of Homer, Thucydides, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. They saw no essential discontinuity between themselves and classical Greece. It was now Justinian’s responsibility to see that the essential base of such a classical pedagogical system was maintained.Classical literature had proven its worth over many centuries, and was to survive alongside with Christianity. In the Christian Roman Empire Justinian hoped to shape what one could read and learn, and teach the classics, but only if he or she was Christian first.

Nikolaos Provatas

Associate Research Physicist, Departments of Physics and Mechanical Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.